A Boy With Right Lower Quadrant Pain: What’s the Cause?

An 8-year-old previously healthy boy presented with a poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, and intermittent abdominal pain. He had had a poor appetite for approximately 24 hours, with intermittent nausea and 5 episodes of nonbloody, nonbilious emesis in the last 12 hours. He had developed right lower quadrant (RLQ) abdominal pain approximately 6 hours before presentation. The pain was sharp, moderate, and worsened by activity, such as running and playing basketball.

He denied any fever, diarrhea, constipation, cough, sore throat, dysuria, or hematuria. There was no history of trauma.

The patient had been born at 35 weeks of gestation with a small atrial septal defect, which had closed spontaneously at 12 months of age. He had been healthy and had been on no medications. His vital signs included a temperature of 37.6°C, heart rate of 120 beats/min, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, oxygen saturation of 100%, blood pressure of 111/65 mm Hg, and weight of 38 kg.

On physical examination, he was alert and well appearing. He ambulated well. He had dry mucous membranes but no intraoral lesions or posterior pharyngeal erythema, edema, or exudate. His cheeks were flushed. Respiratory and cardiovascular examination findings were normal. His abdomen was soft and nondistended.

The patient pointed to his RLQ and stated that it hurt, but there was only minimal RLQ tenderness to palpation. There was no rebound tenderness or guarding. He had a negative Rovsing sign and a negative obturator sign, but he had a positive psoas sign.

Bowel sounds were normal, as were the results of a genital examination. No costovertebral angle tenderness was elicited. There was no pallor, jaundice, or rash. Neurologic and musculoskeletal examination findings were normal. Computed tomography (CT) results are shown here and on the next pages.

What is causing the boy’s sudden illness?

A. Viral gastroenteritis with mesenteric adenitis

B. Acute appendicitis

C. Nephrolithiasis

D. Constipation

(Answer and discussion on next page)

Answer: B, acute appendicitis

The patient’s initial appendix ultrasonogram showed a 3-mm tubular structure in the RLQ, which was compressible and consistent with a normal appendix. No free fluid, mass, or lymphadenopathy was present. Results of urinalysis showed a ketone level of 160 mg/dL and a small amount of blood. The patient had one emesis after an oral dose of ondansetron and the start of intravenous fluid. His white blood cell (WBC) count was 22,500/µL, with 76% neutrophils and 12% lymphocytes.

Although the patient felt better and wanted to go home, he was admitted the pediatric floor of the local hospital for observation and serial abdominal diagnostic radiographic examinations.

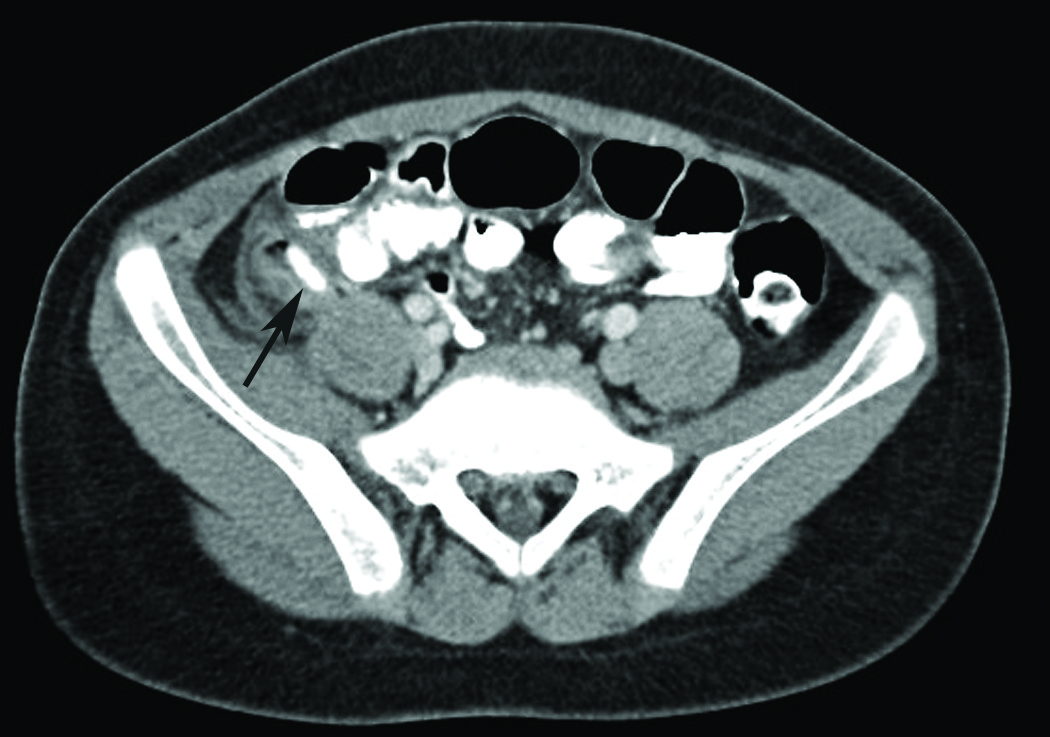

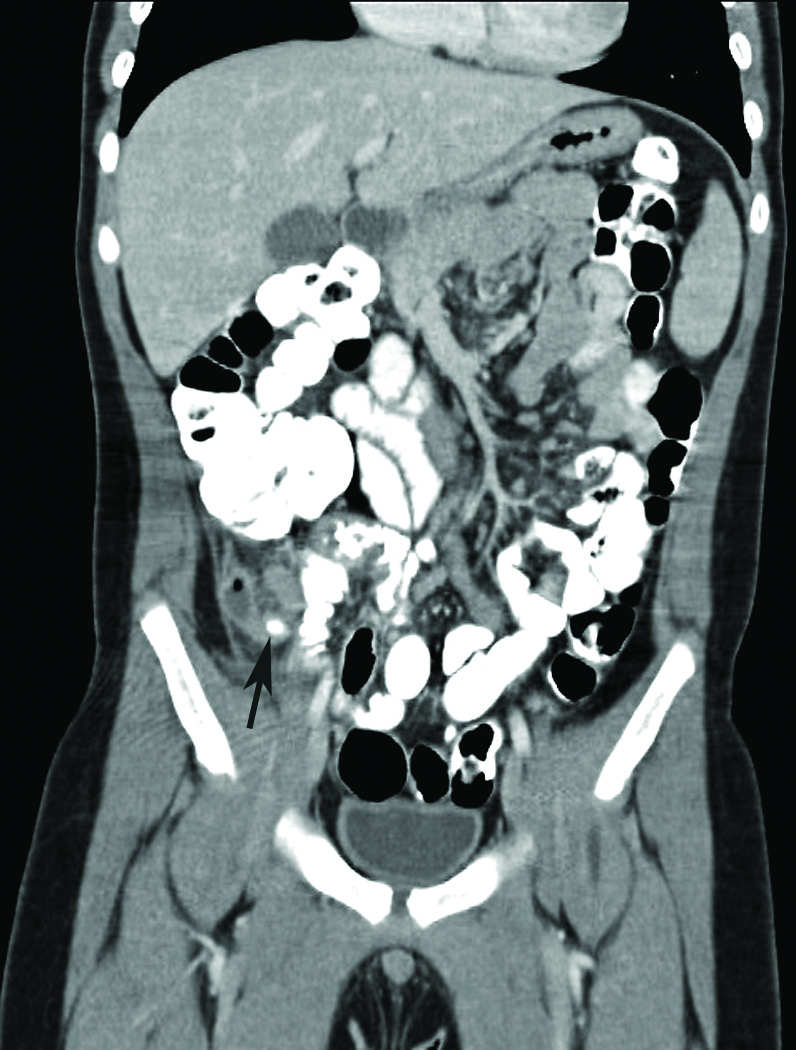

He did well initially, but 8 hours after admission he developed severe RLQ pain. An abdominal CT was done (Figures), and the findings indicated acute appendicitis with a 1.4-cm appendicolith. Distal to the appendicolith, an enlarged, dilated fluid collection measuring 1.3 cm in diameter was seen, containing multiple foci of gas although maintaining a curvilinear shape. This might have represented inflammatory material in the distal appendiceal walls; however, early rupture into a small periappendiceal abscess could not be excluded.

The patient underwent laparoscopic appendectomy. The surgeons noted that the boy had “a curled up and partially retrocecal appendix, with severely inflamed tip that was adherent to the lateral abdominal wall.”

During his 48-hour hospitalization, he was treated with intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam and then completed a 10-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanate after discharge home. He did well, with no complications.

Diagnosis

Appendicitis can be difficult to diagnose in young children for several reasons. The classic symptoms of appendicitis (eg, anorexia, vague periumbilical pain followed by RLQ pain, fever, vomiting) are present in less than 60% of pediatric patients. Moreover, a lack of migration of pain to RLQ occurs in 50% of children with appendicitis; anorexia is absent in 40% of patients, and rebound tenderness is absent in 52% of patients. Unlike in adults with appendicitis, vomiting often precedes abdominal pain in children.

Approximately 44% of pediatric patients diagnosed with appendicitis present with 6 or more of the following atypical features1:

• Absence of maximal pain in RLQ

• Abrupt onset of pain

• No migration of pain

• No guarding

• No rebound pain

• No percussive tenderness

• Negative Rovsing sign

• No anorexia

• No fever

• Normal or increased bowel signs

An estimated 15% of patients with retrocecal appendicitis do not have signs and symptoms localized to the RLQ but instead localized to the psoas muscle. They typically have vomiting prior to pain (owing to irritation of the nearby duodenum). They may have no pain until the appendicitis is advanced or the appendix perforates. A psoas sign is especially helpful in these patients.

Patients with the tip of the appendix deep in the pelvis (pelvic appendicitis) may have signs and symptoms localized to the rectum or the bladder and can present with diarrhea or dysuria. The obturator sign is particularly helpful in these patients. Patients with a medially positioned appendix may have suprapubic pain, whereas patients with a laterally positioned appendix may have flank pain.

The WBC count is elevated in 70% to 90% of patients with appendicitis, but the value often is within the normal range in the first 24 hours of symptom onset. Elevation occurs when the disease progresses. Elevation of segmented neutrophils or bands with a normal total WBC count may support the diagnosis of appendicitis. A WBC count greater than 15,000/µL compels evaluation and suggests perforation of the appendix.

Ultrasonography

According to a recent observational study of 263 children between the ages of 4 and 17 years with suspected appendicitis, ultrasonography was inaccurate in 101 cases (88 false positives, 13 false negatives). This was particularly true for children with a body mass index above the 85th percentile or with low pretest clinical suspicion for appendicitis.2 Appendix ultrasonography visualization rates in children vary from 22% to 98%, with sensitivity ranging from 74% to 100% and specificity ranging from 88% to 90%.

Ultrasonography for the diagnosis of appendicitis has a number of limitations. Fat absorbs and diffuses the ultrasound beam, making it more difficult to scan children who are overweight. It can be difficult to identify an appendix that is only focally inflamed (tip appendicitis). In addition, gaseous distention of the intestines overlying the appendix makes the appendix more difficult to visualize. Pain and/or anxiety make ultrasonography difficult in some children.

The bottom line: Negative ultrasonography results in the presence of persistent signs and symptoms suggestive of appendicitis are insufficient to reliably exclude appendicitis.

Gastroenteritis

Children with acute gastroenteritis typically develop fever, cramping, abdominal pain, and diffuse abdominal tenderness before diarrhea begins. While the severity of the pain can mimic other more serious conditions (eg, appendicitis), the onset of diarrhea generally clarifies the etiology. Many patients have nausea and vomiting.

Gastroenteritis can be caused by viruses, bacteria, or parasites; clinical manifestations depend on the organism. Most cases are caused by viruses. Yersinia enterocolitica gastroenteritis can cause focal RLQ abdominal pain and peritoneal signs that are clinically indistinguishable from appendicitis.Most cases of gastroenteritis in children are self-limited and do not require laboratory evaluation. All patients require fluid and electrolyte replacement therapy to prevent dehydration.

Mesenteric Lymphadenitis

Mesenteric lymphadenitis is an inflammatory condition of the mesenteric lymph nodes that can present with acute or chronic abdominal pain. Because the nodes usually are in the RLQ, mesenteric lymphadenitis sometimes mimics appendicitis. Mesenteric lymphadenitis is diagnosed with an ultrasonogram that shows abdominal lymph nodes greater than 10 mm. The presence of enlarged lymph nodes on diagnostic images does not by itself exclude a diagnosis of appendicitis; it is necessary to demonstrate a normal appendix, as well.3 Etiologies of mesenteric lymphadenitis include viral and bacterial gastroenteritis (eg, Y enterocolitica), group A streptococcal pharyngitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and lymphoma. Viral infection is most common.

Constipation

Constipation is common in children and can present with fecal impaction and severe colicky lower abdominal pain. In a series of 83 children presenting with acute abdominal pain to primary care providers or an emergency department, acute or chronic constipation was the most common underlying cause, occurring in 48% of children.4 In many cases, rectal examination was a key step in establishing the diagnosis.

Constipation is likely in children with at least 2 of the following characteristics: fewer than 3 stools weekly, fecal incontinence (usually related to encopresis), large stools palpable in the rectum or through the abdominal wall, retentive posturing, or painful defecation.4 Parents might not recognize the relationship of constipation to the child’s abdominal pain.

Nephrolithiasis

Most children with nephrolithiasis present symptomatically, usually with flank or abdominal pain and/or gross hematuria. Approximately 20% of children are asymptomatic; primarily, children younger than 6 years of age get a diagnosis when stones are detected during abdominal imaging done for other purposes.5

Pain can be located either as abdominal or flank pain and varies with age. The age-related difference in pain might be related to stone location at presentation. Younger children (less than 5 years of age) are less likely to have ureteral stones than are school-aged children and adolescents. Ureteral stones generally are painful, since they cause ureteral obstruction, whereas kidney stones often are asymptomatic and might be diagnosed as an incidental finding on abdominal imaging.

The intensity of pain can vary from a mild ache to severe, debilitating pain. In children younger than 5 years of age, the pain, if present, appears to be milder and is nonspecific. In addition, young children often are unable to articulate the location and severity of the pain. As a result, young children frequently are evaluated for other causes of abdominal pain before the diagnosis of nephrolithiasis is made. From 30% to 55% of children with nephrolithiasis present with gross hematuria. Approximately 10% present with symptoms of dysuria and urgency suggestive of a urinary tract infection.6 In addition to these symptoms, nausea and vomiting have been described as presenting symptoms in 10% of patients.

Dr Myslenski is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University and an attending physician in the department of emergency medicine at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio. Dr Effron is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Case Western Reserve University, an attending physician in the department of emergency medicine at MetroHealth Medical Center, and a consultant emergency physician at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, all in Cleveland, Ohio.

William Yaakob, MD—Series Editor: Dr Yaakob is a radiologist in Tallahassee, Florida.

References:

1. Becker T, Kharbanda A, Bachur R. Atypical clinical features of pediatric appendicitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(2):124-129.

2. Schuh S, Man C, Cheng A, et al. Predictors of non-diagnostic ultrasound scanning in children with suspected appendicitis. J Pediatr. 2011;158(1);112-118.

3. Simanovsky N, Hiller N. Importance of sonographic detection of enlarged lymph nodes in children. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26(5):581-584.

4. Loening-Baucke V, Swidsinski A. Constipation as cause of acute abdominal pain in children. J Pediatr. 2007;151(6):666-669.

5. VanDervoort K, Wiesen J, Frank R, et al. Urolithiasis in pediatric patients: a single center study of incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. J Urol. 2007;177(6):2300-2305.

6. Sternberg K, Greenfield SP, Williot P, Wan J. Pediatric stone disease: an evolving experience. J Urol. 2005;174(4 pt 2):1711-1714.