Even in the winter, children should be encouraged to play outdoors. Such exercise has significant cardiovascular and musculoskeletal benefits. However, those benefits must be weighed against the risk of potential localized or systemic consequences of excessive exposure to cold. Hypothermia is life-threatening. Localized injuries are typically less severe but may be accompanied by generalized hypothermia and are associated with great morbidity and even death (Table 1).

By understanding the epidemiology and pathophysiology of hypothermia, cold-related deaths can be prevented.1 Here we describe effective preventive measures. We also review various types of cold injuries and discuss their treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGYHypothermia is defined as a core temperature at or below 35ºC (95ºF).2 It can be categorized as:

• Mild: 34ºC to 35ºC (93ºF to 95ºF).

• Moderate: 30ºC to 34ºC (86ºF to 93ºF).

• Severe: less than 30ºC (86ºF).

Certain factors--such as age or preexisting medical conditions--increase the risk of hypothermia (Table 2). Hypothermia is not limited to the northern states: other areas of the country with milder climates (the Carolinas and Virginia, for example) have also reported deaths from hypothermia.3,4 The majority of these deaths occur in November through February.1 Each year, approximately 500 deaths are attributed to hypothermia; about half the victims are 65 years or older and two thirds are male.4 Fortunately, fewer than 20 children younger than 20 years die every year of overexposure to the cold: the vast majority of these deaths are preventable.4 Children at highest risk for death secondary to hypothermia include infants younger than 1 year, boys in early adolescence, and inadequately dressed older adolescents who abuse alcohol( or illicit drugs.2,4

Certain factors--such as age or preexisting medical conditions--increase the risk of hypothermia (Table 2). Hypothermia is not limited to the northern states: other areas of the country with milder climates (the Carolinas and Virginia, for example) have also reported deaths from hypothermia.3,4 The majority of these deaths occur in November through February.1 Each year, approximately 500 deaths are attributed to hypothermia; about half the victims are 65 years or older and two thirds are male.4 Fortunately, fewer than 20 children younger than 20 years die every year of overexposure to the cold: the vast majority of these deaths are preventable.4 Children at highest risk for death secondary to hypothermia include infants younger than 1 year, boys in early adolescence, and inadequately dressed older adolescents who abuse alcohol( or illicit drugs.2,4

The most clinically significant type of localized cold injury in the pediatric population is frostbite, which implies actual freezing of tissue. Like burns, frostbite is rated by degrees (see Table 1). First degree is the mildest and most superficial type. Fourth-degree frostbite involves the freezing of subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and bone.

The number of cases of localized cold injuries that occur per year nationally is unknown. The American Red Cross predicts that thousands of people can expect to experience frostbite in the winter months.5 The burden of this cold- related problem outside the United States is revealed in a study from Finland: the authors reported that the lifetime and annual incidence of frostbite among military servicemen (some as young as 17) was 44% and 2.2%, respectively.6

PATHOPHYSIOLOGYHuman core temperature is normally maintained within 0.6ºC (1ºF). Hypothermia occurs when the body's ability to conserve adequate heat is overwhelmed. Heat is lost via radiation, conduction, convection, and evaporation. The reaction of the hypothalamus to neural feedback from environmental sensations is the key component of temperature regulation. Changes in cutaneous circulation help maintain core body temperature. Radiation or heat transfer from a relatively warm body into a colder environment is responsible for the majority of heat lost. This phenomenon is particularly important in infants and young children because of their greater body surface area-to-mass ratio. When a child is in cold and wet clothing or submerged in cold water (such as in drowning), heat loss is increased through conduction. Through convection (which accounts for the wind chill index), cold wind also increases heat loss. Evaporation is a source of heat loss, particularly for a newborn immediately after birth in the delivery room.

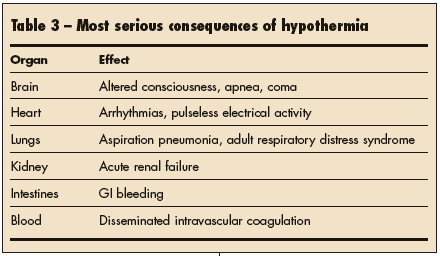

Normally, peripheral vasoconstriction occurs when the ambient temperature is about 15ºC (59ºF).7 Other generalized bodily responses include sweating cessation, shivering, and release of such chemicals as epinephrine( and thyroxine to increase heat production. The body's intense response to persistent cold leads to significant adverse effects on the major organ systems (Table 3).

Peripheral vasoconstriction di- verts blood to the kidneys, which causes an initial diuresis with resultant decreased intravascular volume. Blood flow to the brain is eventually decreased, resulting in CNS depression of various degrees. CNS abnormalities are progressive. Each drop in temperature of 1ºC produces a 6% to 7% decline in cerebral blood flow.8

The heart responds with initial tachycardia; eventually, bradycardia and arrhythmias ensue. Apnea, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and aspiration pneumonia are serious pulmonary consequences. The metabolic acidosis, respiratory acidosis, hypokalemia, and hypoglycemia that accompany severe hypothermia wreak havoc on all bodily functions. Coma, cardiac and renal failure, and respiratory arrest are the end points if the hypothermia is untreated.

Localized cold injuries in children result mainly from inadequate protection against the environment. The most peripheral body parts (fingers, nose, ears, toes), which contain abundant arteriovenous anastomoses that shunt blood to the body's core, are the most vulnerable to injury. Cold objects (eg, a popsicle or ice pack) placed against the skin for prolonged periods can also injure the skin (Figure 1).9 Local damage occurs when tissue temperature drops to 0ºC (32ºF) (Figure 2).7

A freezing cascade that leads to frostbite has been described7:

• The first, or prefreeze, phase involves the loss of skin sensation, vascular constriction, and endothelial plasma leakage.

• The development of ice crystals in the extracellular fluid causes water to move out of cells: the result is cell shrinkage and collapse during the second, or freeze-thaw, phase.

• The third, or vascular stasis and progression of ischemia, phase is characterized by endothelial cell damage, necrosis, and sloughing of dead tissue in the affected area.7

The stasis and thrombosis that occur in the affected body part provide a conducive environment for gangrene. Sequelae of frostbite depend on the depth of damage sustained. First-degree frostbite can lead to telangiectasias,10 for example, while the most severe types lead to permanent disability (arthritis, premature epiphyseal closure), disfigurement (deformed digits), or amputation of the involved body part.11,12

HYPOTHERMIA

The history. A detailed account of the child's symptoms and accompanying environmental conditions usually suggests the diagnosis of hypothermia. Accidental hypothermia may occur indoors in poorly heated homes or outdoors. Those affected may include scantily dressed toddlers who wander outdoors, lost mountain climbers, hikers, backpackers, skiers, and near-drowning victims.13 In the hospital setting, iatrogenic hypothermia may occur during neonatal resuscitations.

The medical history should focus on any underlying medical conditions. When evaluating a cold-injured child, 2 initial steps are crucial:

• Measure vital signs, including the core body temperature with a low-reading thermometer.

• Provide the ABCs of emergent care.

Examine the child for clinical features of hypothermia or frostbite. In mild hypothermia, the patient may appear fatigued and display persistent shivering, ataxia, clumsiness, and confusion. Tachypnea and tachycardia are usually present.14

The child with moderate hypothermia will not be shivering (the body loses its ability to warm itself). Declining mental status may cause the freezing patient to remove clothing (a phenomenon known as paradoxical undressing). An irregular heartbeat is likely at this stage.14

In severe hypothermia, apnea, stupor, and coma are probable features. Cardiac monitoring may reveal pulseless electrical activity, atrial fibrillation, ventricular ectopy, or even asystole.15

Frostbite may occur alone or concurrently with hypothermia. Typically, the patient is a child who is experiencing discomfort or an abnormal sensation in a peripheral body part after being outdoors in cold weather for a lengthy period. A physical examination that focuses on the dermatologic and neurovascular condition of the symptomatic body part provides clues to the degree of frostbite present (see Table 1).

Management in the field.First and foremost, the rescuers must ensure their own safety before any rescue attempt is made. Mild hypothermia can be managed in the field with passive rewarming techniques. These include drying the patient, using warm blankets, and placing the patient in a warm environment. Passive rewarming could possibly be done by companions of the victim.

The severely hypothermic child requires more aggressive treatment. He or she must be handled as gently as possible to prevent arrhythmia. Wet clothing needs to be removed and the child placed in a warm, dry environment. Airway protection via endotracheal intubation is typically required in moderate to severe hypothermia because it facilitates cardiopulmonary resuscitation and tracheal toileting.

Because hypothermia causes a left shift of the oxygen dissociation curve, administration of oxygen and close cardiac monitoring are mandatory. Antiarrhythmic medications and defibrillators are effective only at body temperatures of 28ºC (82.4ºF) or higher.15 A nasogastric tube may be needed to help with gastric drainage secondary to gastric paresis.12 The hypothermic child should be transported to an emergency or tertiary care facility as soon as possible.

In the hospital. Ideally, a physician experienced in emergency medicine or pediatric intensive care should manage the hospitalized cold-injured child. If CPR has been initiated, it is continued with close cardiac and laboratory monitoring. Severe cardiac and metabolic abnormalities are likely (Table 4). Osborne waves, or J waves (secondary waves that follow the S wave), are seen in severe hypothermia (Figure 3). The magnitude of the wave increases as the severity of hypothermia increases.12

Radiographs of the chest should be taken to evaluate endotracheal tube placement and to confirm or rule out aspiration. Radiographs of injured areas may also be required if accompanying fractures are suspected.

Radiographs of the chest should be taken to evaluate endotracheal tube placement and to confirm or rule out aspiration. Radiographs of injured areas may also be required if accompanying fractures are suspected.