Lipomyelomeningocele

A girl was born by spontaneous vaginal delivery at 40 weeks of gestation to a 28-year-old woman, gravida 2, para 1. The newborn’s 1-minute and 5-minute Apgar scores were both 9. The infant's prenatal history and laboratory profile results were normal.

A remarkable finding at the neonate’s initial physical examination was a 3×4-cm midline sacral swelling, which was soft, had overlying blotchy erythema, and did not blanch with pressure (A and B). The newborn was neurologically intact; lower-extremity tone was good, with symmetric movements and a quick withdrawal reflex. The patellar reflexes were present and equal. There was no ankle clonus. There was a good urine stream, and an anal wink was present.

A remarkable finding at the neonate’s initial physical examination was a 3×4-cm midline sacral swelling, which was soft, had overlying blotchy erythema, and did not blanch with pressure (A and B). The newborn was neurologically intact; lower-extremity tone was good, with symmetric movements and a quick withdrawal reflex. The patellar reflexes were present and equal. There was no ankle clonus. There was a good urine stream, and an anal wink was present.

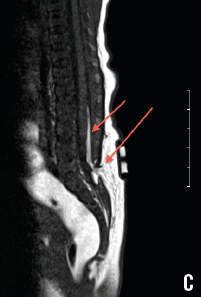

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine (C) confirmed a defect at the posterior elements of L5, and a suspected tethered cord with fat seen in the posterior epidural space.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine (C) confirmed a defect at the posterior elements of L5, and a suspected tethered cord with fat seen in the posterior epidural space.

Lipomyelomeningocele, or spinal cord lipoma, is one of the closed neural tube defects. Premature disjunction of the cutaneous ectoderm and neuroectoderm allows mesodermal infiltration, resulting in a tethered spinal cord attached to a benign fatty tumor in the back.1 The term occult spinal dysraphism often is used to describe these skin-covered lesions.

Thorough skin examination of a newborn is important, because the majority of these occult conditions are associated with some anomaly of the overlying skin.2 Because sacral dimples are the most encountered cutaneous finding associated with occult spinal dysraphisms, they should be evaluated carefully if they are found outside the sacrococcygeal region or are located more than 2.5 cm above the anal verge.

Thorough skin examination of a newborn is important, because the majority of these occult conditions are associated with some anomaly of the overlying skin.2 Because sacral dimples are the most encountered cutaneous finding associated with occult spinal dysraphisms, they should be evaluated carefully if they are found outside the sacrococcygeal region or are located more than 2.5 cm above the anal verge.

Multiple dimples or any associated neurologic deficits warrant further evaluation with imaging.1 Either ultrasonography or MRI can be used to investigate occult spinal dysraphism; in general, MRI of the spine is indicated if ultrasonography results are abnormal.

Unlike an open neural tube defect, a lipomyelomeningocele is not a neurosurgical emergency; however, prompt referral for evaluation is recommended. Neurologic disturbances such as bladder dysfunction can be difficult to demonstrate in neonates. Therefore, any cutaneous finding of occult spinal dysraphism, even in a neurologically intact child, justifies a thorough neonatal assessment and strict periodical neurologic monitoring aimed at early detection upper motor neuron signs.3

Appropriate follow-up with pediatric neurosurgery for initial assessment, monitoring, and the timing of surgery, if needed, should be arranged before the neonate is discharged.

The patient in our case was scheduled for outpatient follow-up and was then discharged from the hospital in good condition.

References:

1.Zywicke HA, Rozzelle CJ. Sacral dimples. Pediatr Rev. 2011;32(3):109-113.

2.McLone DG, Thompson DNP. Lipomas of the spine. In: McLone DG, ed. Pediatric Neurosurgery: Surgery of the Developing Nervous System. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 2001:289-301.

3.Cornette L, Verpoorten C, Lagae L, et al. Tethered cord syndrome in occult spinal dysraphism: timing and outcome of surgical release. Neurology. 1998;50(6):1761-1765.

Deepak M. Kamat, MD, PhD—Series Editor:Dr Kamat is professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University in Detroit. He is also director of the Institute of Medical Education and vice chair of education at Children’s Hospital of Michigan, both in Detroit.