Peer Reviewed

Pheochromocytoma in the Elderly

An 89-year-old man presented with progressive shortness of breath, weakness, decreased appetite, weight loss, and episodes of falling and intermittent lower extremity swelling. Review of systems revealed no orthopnea, cough, chest pain, fevers, sweats, headaches, syncope, palpitations, or abdominal pains.

His history included complete heart block with pacemaker, peripheral vascular disease, hypercholesterolemia, and a remote history of tuberculosis. The patient did not have a known history of hypertension and had been started on a beta-blocker at the time of a revision of the pacemaker. He had a history of remote tobacco use 60 years ago, no alcohol use, and a history of working in the shipyard with asbestos exposure.

Family history was negative for refractory hypertension, or endocrine disorders. Home medications included metoprolol, simvastatin, finasteride, calcium, vitamin D, and aspirin.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

RELATED CONTENT

Skin Disorders in Older Adults: Benign Growths and Neoplasms

Images of Malignancy

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

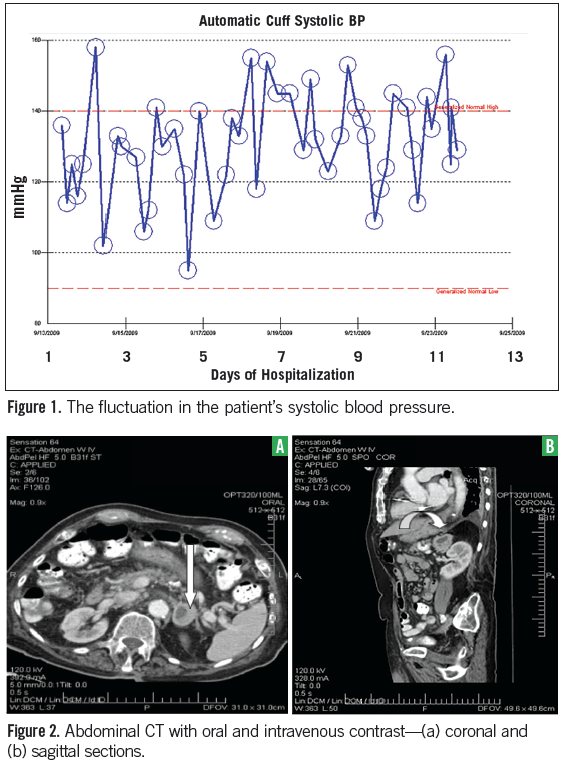

Physical Examination

The patient was a comfortable elderly gentleman who appeared mildly chronically ill. Vital signs included a temperature of 35.8°C, pulse of 61 beats per minute, blood pressure of 102-156/44-79 mm Hg (Figure 1), respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, pulse oximetry at 97% on room air, and orthostatic blood pressures were normal. His weight was 75 kg and a body mass index of 28.

His exam was notable for no hyperpigmentation, thyroid gland was not enlarged with no focal nodularity, no lymphadenopathy, lungs clear on auscultation, heart sounds regular with a 1/6 systolic murmur at the left sternal border, abdomen soft with no masses, extremities showed chronic stasis changes, and no pedal edema.

Laboratory Tests

An EKG showed a normal sinus paced rhythm. The chest x-ray was normal. CT scan of the chest showed multiple pulmonary nodules, primarily in the bilateral lung apices with speculation measuring 6 mm to 7 mm, with mediastinal hilar and axillary adenopathy, and a 3 cm left adrenal mass with no evidence for pulmonary emboli. Subsequent CT scan of the abdomen showed the 2.8 cm x 3.7 cm left adrenal lesion (Figures 2a and 2b).

The patient was seen by oncology and thoracic surgery consultation services. The patient had a core biopsy of the left adrenal mass prior to hormonal assessment. The pathology was consistent with pheochromocytoma with immunostains for synaptophysin and chromogranin strongly positive (Figure 3). The endocrine service was alsoconsulted.

Laboratory tests were significant for negative troponins, proBNP at 722 pg/mL, potassium at 3.9 mmol/L (normal: 3.5-5.1 mmol/L), creatinine at 0.7 mg/dL (normal: 0.5-1.3 mg/dL), glucose at 125 mg/dL, calcium at 8.5 mg/dL (normal: 8.5-10.1 mg/dL), white blood count at 10,000/µL (normal: 4.7-11), hemoglobin at 12.7 g/dL (normal: 13.2-18 g/dL), platelets at 137,000/µL (normal: 189-440), thyroid stimulating hormone levels at 1.6 µIUNIT/mL (normal: 0.4-4), and the adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test was normal. Plasma and urine tests for pheochromocytoma were consistent with the pathologic diagnosis (Table).

(Discussion on next page)

Follow-Up

Additional workup to rule out metastasis was negative, including a CT head, bone scan, PET scan, and thoracentesis. Echocardiography showed normal systolic function, but impaired relaxation. Pursuing further investigations, including lung nodule biopsy, was discussed in-depth with the patient and his family. The beta-blocker was discontinued with stability in the blood pressure.

Given the patient’s age, general debility, and the size of the nodules, the decision was made to follow the patient conservatively with plan for follow-up CT of chest and abdomen.

Discussion

The pathologic finding of pheochromocytoma was unexpected given the patient’s age, normal blood pressure, and limited symptomatology suggestive of the diagnosis. In addition, the biopsy was done to assess for the possibility of metastatic lung cancer without preprocedure biochemical assessment of the adrenal gland. The patient tolerated the procedure without difficulty, but was at risk. The patient’s symptoms while on beta-blockers may have been the only clinical clue prior to the diagnostic workup.

Phoechromocytoma is an endocrine neoplasm that originates from chromaffin cells in the adrenal glands or sympathetic paraganglia. Although it is a very rare cause of hypertension,1 it is present in 85% to 95% of patients with pheochromocytoma. Peak incidence is between the third and fifth decades of life, and it is considered as unusual diagnosis in the elderly. More than 90% of pheochromocytomas are located within the adrenal glands and 98% in the abdomen.2

These tumors can give a wide range of manifestations depending on their functionality, size, comorbidities, and age of the patient. Patients may be completely asymptomatic, with estimated 10% of cases are clinically silent.2 The average time from the onset of hypertension to the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma is 3 years.3 The effect of catecholamines and its metabolites can lead to diverse presentations. The classic triad of episodic headache, sweating, and palpitation is not always present.4,5 Pulmonary edema can result from cardiomyopathy or may be due to pulmonary venoconstriction and altered pulmonary capillary permeability.6

Many authorities recommend plasma fractionated metanephrines as the screening tool of choice if the pretest probability is high (eg, spells, vascular mass, high Hounsfield unit density on noncontrast CT scan, marked enhancement with delayed washout after contrast).7 This is especially emphasized when hereditary pheochromocytoma is suspected, where this test has a reported sensitivity and specificity of 97% and 96%, respectively. In sporadic pheochromocytoma, the test has a reported sensitivity of 99% but a specificity of 82%; the total urinary metanephrines had a better specificity at 89% in this setting.8

Before biopsying any adrenal mass, functional assessment must be done and the patient prepared accordingly. The adrenal incidentalomas have been found in at least 2% to 3% of patients undergoing abdominal CT, and pheochromocytomas are reported to occur in about 5.1% to 23.0% of those patients.9 Any procedure or surgery, in the presence of a functional pheochromocytoma, may have deleterious outcome if not properly addressed.

Treatment. Once diagnosed, treatment options depend on symptoms, complications, presence or absence of hypertension, whether the tumor is benign or malignant, and the clinical status of the patient. Nonselective alpha-blockers are the preferred choice to treat hypertension. This is particularly important preoperatively, because of the risk for pheochromocytoma crisis, with potential arrhythmias, malignant hypertension, and death.2 Initiation of beta-blockers is associated with deterioration in hemodynamics and labile blood pressure.6

Literature. Although pheochromocytoma may not be often considered in the elderly, the literature reveals a significant amount of incidentally diagnosed disease (at autopsy or radiologically). In a clinical series of 155 patients, 9% were 60 years or older.10 In a review of a 50-year autopsy series from Mayo Clinic, 41 of 54 autopsy-proven cases were unsuspected during life. Of those with postmortem diagnosis, only 54% had hypertension. Twelve patients (22%) were older than 68 years; in 9 of them, the diagnosis was made after death.8

A retrospective study, which included 439 patients with pheochromocytoma registered in Sweden from 1958 to 1982, found that the average age at diagnosis in those whose disease was discovered before death was 48.5 years versus 65 years for those diagnosed at autopsy.8 These data suggest that pheochromocytoma in the geriatric population may have a silent clinical course more commonly than in the younger patients. Age-dependent modification of catecholamine metabolism might play an important role.10 The change of baroreceptors and other receptors in different target organs, associated with aging is also a potential factor. In addition, the presence of comorbidities, especially of the cardiovascular, neurological, and renal systems may confound the whole picture and make the diagnosis in this age a real challenge.

Although normal blood pressure is present in 5% to 15% of all patients with pheochromocytoma, this number is much higher in incidentally found tumors and in patients undergoing screening because of a family history of pheochromocytoma, von Hippel-Lindau disease, or suspected multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2.5,11,12 Patients with genetic predisposition are generally younger and more likely to be normotensive.13

Due to the widespread use of CT scans worldwide, more cases with normal blood pressure and/or atypical clinical picture may be seen, probably because of early detection and incomplete catecholamine effects. Normotension could possibly be a result of associated hypovolemia, compensating for the vasoconstriction. Another explanation is the fact that other than catecholamines, these tumors secrete different types of other substances, including calcitonin, somatostatin, neurotensin, adrenocorticotropin, lipotropin, neuropeptide Y and, vasoactive intestinal peptide. The vasodilating characteristics of some of these may contribute to the normal blood pressure.14 In addition, epinephrine-secreting tumors can cause episodic hypertension and sometimes hypotension.6,15

Outcome of the Case

In our patient, the initiation of beta-blockers 1 year before the diagnosis may have precipitated or potentiated his episodes of shortness of breath, falls, and lower extremity edema, and made these clinically overt. Nonselective beta-blockade leads to loss of beta 2 receptor-mediated vasodilatation and the unopposed effects of alpha receptors causes vasoconstriction, leading to arterial hypertension, which increased after load, causing myocardial dysfunction and pulmonary edema.6

Acknowledgements

The pathology slide was provided by Dr. Deepa Dutta from the pathology department at The Sinai Hospital of Baltimore. Some of the material was presented as a poster at the Endocrine Society meeting in San Diego in June 2010.

Naseem M. Sunnoqrot, MD, specializes in internal medicine at The Johns Hopkins University-Sinai Hospital in Baltimore, MD.

Asha Thomas, MD, is a physician in the divisions of endocrinology at The Sinai Hospital of Baltimore and The John Hopkins University School of Medicine, both in Baltimore, MD.

References:

1.Tam V, Ng KF, Fung LM, et al. The importance of the interpretation of urine catecholamines is essential for the diagnosis and management of patient with dopamine-secreting paraganglioma. Ann Clin Biochem. 2005;42:73-77.

2.Blake M, Kalra M, Maher M, et al. Pheochromocytoma: an imaging chameleon. RadioGraphics. 2004;24(1):S87-S99.

3.Ilias J, Pacaka K. Clinical overview of pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas and carcinoid tumors. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35(Suppl 1):S27-S34.

4.Stein PP, Black HR. A simplified diagnostic approach to pheochromocytoma. A review of the literature and report of one institution's experience. Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70(1):46-66.

5.Guerrero MA, Schreinemakers JM, Vriens MR, et al. Clinical spectrum of pheochromocytoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209(6):727-732.

6.Sibal L, Jovanovic A, Agarwal SC, et al. Phaeochromocytomas presenting as acute crises after betablockade therapy. Clin Endocrinol. 2006;

65:186-190.

7.Pomares FJ, Cañas R, Rodríguez JM, et al. Differences between sporadic and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 A phaeochromocytoma. Clin Endocrinol. 1998;48:195-200.

8.Bravo E, Tagle R. Pheochromocytoma: state-of-the-art and future prospects. Endocr Rev. 2003;24(4):539-553.

9.Shen SJ, Cheng HM, Chiu A, et al. Clinically silent pheochromocytomas: report of four cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2005;28(1):44-50.

10.Januszewicz W, Chodakowska J, Styczynski G. Secondary hypertension in the elderly. J Hum Hypertens. 1998;12(9):603-606.

11.Young WF Jr, Maddox DE. Spells: in search of a cause. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:757-765.

12.Neumann HP, Pawlu C, Peczkowska M, et al. Distinct clinical features of paraganglioma syndromes associated with SDHB and SDHD gene mutations. JAMA. 2004;292(8):943-951.

13.Adler JT, Meyer-Rochow GY, Chen H, et al. Pheochromocytoma: current approaches and future directions. Oncologist. 2008;13(7):779-793.

14.Sukor N, Saidin R, Kamaruddin NA. Epinephrine-secreting pheochromocytoma in a normotensive woman with adrenal incidentaloma. South Med J. 2007;100(1):73-74.

15. Page LB, Raker JW, Berberich FR. Pheochromocytoma with predominant epinephrine secretion. Am J Med. 1969;47(4):648-652.