Preventing Permanent Vision Loss: The Diagnosis and Treatment of Temporal Arteritis

AUTHORS:

Leonid Skorin Jr, DO, OD, MS, and Paige Nash, BS

ABSTRACT: Temporal arteritis is a true ocular emergency that may initially present with systemic manifestations to primary care practitioners. If improperly diagnosed, the condition may lead to optic nerve damage, ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and permanent vision loss. This article reviews common findings and provides a recommended treatment course to prevent any permanent vision loss.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Temporal arteritis, also referred to as giant cell arteritis, is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory disorder affecting the major branches of the aortic arch—often including the extracranial arterial branches of the carotid artery.1 The peak incidence of the disease is between the ages of 60 and 75; it is all but unheard of to find temporal arteritis in a patient under the age of 50.1,2 As the general population ages, the incidence of temporal arteritis is rising.1 Females are twice as likely to be affected and patients with the disease are almost always Caucasian.2,3

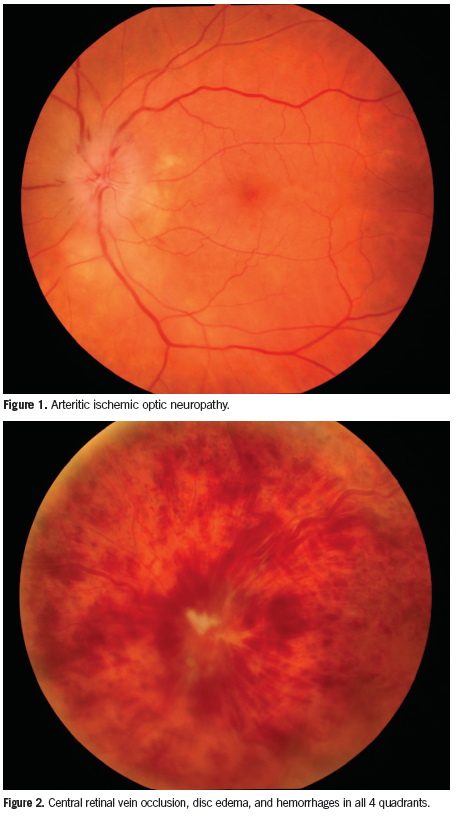

This condition can present a clinical conundrum for primary care practitioners. If left untreated, patients run a significant risk of developing sudden and permanent vision loss, most commonly attributed to arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy (AION, Figure 1).2 However, diagnostic confirmation is not available through noninvasive techniques, which may cause a delay between suspicion and verification of the disease and create a gray area regarding initiation of treatment.

Because temporal arteritis with systemic manifestations may initially present to primary care practitioners, this article reviews common findings and recommended treatment courses to prevent any permanent vision loss.

Symptoms and Differentials

The presenting picture of temporal arteritis can be varied depending on the arteries involved. Temple pain is the most common presenting symptom.2 Other commonly associated symptoms include jaw claudication, scalp tenderness, general malaise, weight loss, and joint pain.4 A new onset headache in a patient over the age of 70 should be considered highly suspicious. Changes in or loss of vision are less frequently noted as presenting symptoms. In patients with polymyalgia rheumatic, a related condition believed to be on a spectrum with temporal arteritis, presenting symptoms are more pronounced in the morning upon awakening and include aching in the neck, shoulders, and pelvic girdle.2

If a patient presents with sudden vision loss, differentials to consider include central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), nonarteritic ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION), inflammatory optic neuritis, and compressive tumor.5 In CRVO, sudden vision loss is accompanied by hemorrhages in all 4 retinal quadrants (Figure 2). Patients with NAION generally have less pronounced vision loss with normal laboratory test results.

Inflammatory optic neuritis presents in patients in the second to third decade of life; thus, the age of onset is the major differentiator between optic neuritis and AION (Figure 3). These patients may also present with pain on eye movements and no systemic symptoms. Compression of the nerve as a result of a tumor will decrease vision gradually. These patients will not have the systemic complaints as individuals with temporal arteritis.5

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of temporal arteritis involves an antigen-immune response in the blood vessel walls. Many inflammatory mediators have been implicated, however, antigens isolated from positive lesions have shown a commonality in the initiating cellular response.6 Unlike atherosclerotic disease, ischemia arises downstream from an occluded vessel resulting from hyperplasia of indigenous cell wall components and not deposition of plaque in the arterial lumen.

Different cells are believed to be involved in the disease process as it occurs in the various layers of the arterial wall. T-cells and T-cell receptors have been detected in adjacent and nonadjacent lesions in temporal arteritis. T-cells and macrophages accumulate in the vessel wall where they produce cytokines and monokines as well as growth factors.6 The cascade of inflammation ensues and ultimately leads to a breakdown in the internal elastic lamina.2 In the presence of this breach, platelet-derived growth factors from multinucleated giant cells stimulate proliferation of the intimal layer. This hyperplastic intimal layer causes the characteristic occlusion of the lumen and downstream ischemia.6

Consequences

Temporal arteritis affects the major branches of the carotid aorta. The aorta is the only site at which the thinning of the vessel media appears to be of concern. This thinning may facilitate an aneurysm in the wall of the aorta.2 In smaller vessels, it is thought that the media thinning is clinically insignificant. Occlusion of the lumen is the source of damage to downstream structures, such as the optic nerve.

Neurologic manifestations—including ischemic stroke—may result secondary to the pattern of vessel involvement and occlusion.2 The pulmonary and coronary arteries may be affected by the disease and myocardial infarction is possible. Persistent headache, malaise, and generalized pain can burden a patient with untreated temporal arteritis.

Sudden, painless, and irreversible vision loss is a potentially devastating consequence that is present in 15% to 20% of temporal arteritis cases.2 Vision loss is most frequently the result of AION, followed by central retinal artery occlusion (Figure 4).7 If left untreated, patients with unilateral vision loss have a 70% chance of developing permanent vision loss in the fellow eye within 1 week.2 Therefore, temporal arteritis is considered a true ocular emergency.

Diagnosis

As soon as temporal arteritis is suspected, steps to confirm the diagnosis and initiate treatment are warranted. Blood work must be ordered to test for elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and platelets.4,8

ESR is a nonspecific measure of inflammation. In response to inflammation, red blood cells show an increased amount of fibrinogen and begin to coalesce into what are known as Rouleaux stacks. These stacks settle out of suspension more quickly than control cells and this rate is measured in millimeters per hour. CRP is produced by the liver in response to inflammation in the body. An increased probability of positive temporal artery biopsy is associated with an ESR in the range of 47 mm/hour to 107 mm/hour and CRP levels >2.45 mg/dL.2,3 Thrombocytosis—ie, platelet count in excess of 400,000 mm3—has been associated with a positive temporal artery biopsy more consistently than ESR and CRP alone. To maximize the validity of these tests, it is imperative that all 3 tests be ordered.8

In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology set forward criteria for the diagnosis of temporal arteritis. A positive diagnosis includes at least 3 of the following criteria: at least 50 years of age, new headache, temporal artery abnormality on palpation, elevated ESR (over 50 mm/hour), and abnormal temporal artery biopsy.9 This method of diagnosis has been criticized because it suggests the classification of patients should be based on a checklist of findings rather than enforcing the importance of temporal artery biopsy as the definitive diagnosis in all suspected cases of temporal arteritis.10

The current gold standard for diagnosis of temporal arteritis is a temporal artery biopsy.2 However, there is a lag time between a physician suspecting a patient of having the disease and the results of the biopsy becoming available to use in the decision making process. If there is a high amount of suspicion based on clinical presentation, it is generally agreed that steroid treatment should be initiated immediately.1,4 Note: There is an approximate 4 week grace period during which the temporal artery biopsy results remain unaltered due to steroid therapy.1,2 If the patient does not receive a biopsy within this window, it may confound treatment decisions going forward. However, without a biopsy result, the physician has no way of knowing if the diagnosis was accurate at the time of initiating steroid treatment, how to determine the best time to taper the steroid, and how to measure treatment success.

Temporal Artery Biopsy

A temporal artery biopsy is done under monitored sedation while the patient remains conscious. The frontal branch of the temporal artery is palpated to locate the area to be excised. The patient’s hair is shaved in the area overlying the vessel of interest. The segment of the vessel to be removed is marked on the skin with a surgical marking pen and then local anesthetic is injected along either side of the vessel. The area is prepped and draped. Once it is ensured that local anesthesia has taken place, a #15 Bard-Parker blade is used to make a shallow incision through the dermis just over the artery. Blunt dissection down to the artery is performed and cautery used throughout this process to maintain hemostasis (Figure 5). The vessel is clamped off using titanium clips or silk sutures at both ends of the isolated specimen. The artery is then excised and sent to pathology. The incision is closed in multilayer fashion.

Most patients tolerate the procedure very well. Facial nerve damage may occur during the excision of the lesion due to proximity of the nerve to the frontal branch of the temporal artery.11 This risk is calculated at approximately 16% and can be decreased substantially if the specimen is collected >35 mm away from the lateral orbital rim. If damaged, the patient may experience a drooping eyebrow and an inability to close the ipsilateral lid. These effects may resolve with time to some degree.12

The reliability of the temporal artery biopsy may be compromised due to skip lesions.13 If the characteristic inflammation does not involve the section of the vessel which was excised in the biopsy, the patient could potentially have “biopsy negative” temporal arteritis (Figures 6 and 7). This is thought to occur in 10% to 30% of temporal arteritis cases. Maximizing the size of the specimen can lower the incidence of false negatives. A length of ≥1.0 cm is recommended with the possibility of false negatives varying inversely with the length of the vessel specimen. Another option to diminish the chance of missing the inflammatory lesions on biopsy is to take specimens from both sides. A disagreement rate of 23% has been found between biopsy results from left and right sides. Traditionally, the specimen is extracted ipsilateral to the side with the symptoms.

Physicians may hesitate to order temporal artery biopsies. Statistics show that management decisions for the patient only change in 10% of cases after results of a biopsy are received. Although this may be true, there are long term benefits to confirming the diagnosis and treatment regimen with a biopsy.

Management

Treatment of temporal arteritis has long been achieved with systemic steroids.3 An oral glucocorticoid dose of 40 mg/d to 60 mg/d is recommended with a long taper schedule.1,2 A reduction of 10% of the initial dose every 1 to 2 weeks in indicated once the disease is believed to be under control. If a patient presents with vision loss, IV methylprednisolone at 250 mg every 6 hours for 3 days is indicated to attempt to halt further vision loss in the involved eye and prevent progression to the fellow eye.1

Most patients achieve remission after 18 months of systemic steroid treatment. Relapses occur in 25% to 65% of treated patients. This is most likely to occur in the first year of treatment and is frequently seen when the steroid taper reaches 7.5 mg/d.14 Some patients may require management with low-dose steroids for up to 7 years.3

Research has suggested that the initial levels of interferon gamma found in the temporal artery walls of patients may correlate to the duration and severity of the disease as well as effective treatment dosage and prolonging of the steroid taper schedule. Indicators such as ESR, CRP, and platelets are monitored to gauge the success of treatment.3 A subsequent increase in ESR during taper does not always necessitate increasing steroid dosage back to a previous level. Data also supports the use of 100 mg/d of aspirin as an adjunct to the steroid therapy to reduce the chance of recurrence.2

There has recently been an interest in investigating the effectivity of steroid-sparing treatments due to the high rate of complications from long-term steroid use—58% of temporal arteritis patients on steroid treatment reported adverse effects. Methotrexate and cyclophosphamide have been trialed in conjunction with steroid management but with insignificant benefits.14,15 Alternating steroid treatment days has been attempted; however, it has been significantly less successful at forcing disease remission than traditional daily dosing. As the pathophysiology of the disease is understood in greater detail, novel options may come to the forefront of research to allow a reduction in the amount of systemic steroids being prescribed for temporal arteritis. At this time, steroids remain the mainstay of treatment.14,15 Vitamin D and calcium have been added to most drug regimens to help counteract the osteoporosis induced by long-term steroid use.3

Temporal arteritis is a true ocular emergency that may initially present with systemic manifestations to primary care practitioners. It is important to be aware of the common findings and the course on which to proceed so as to prevent any permanent vision loss. Temporal artery biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis of temporal arteritis and justify beginning a patient on long-term systemic steroids. As research continues to advance regarding the cellular components and chemical mediators of the inflammatory process behind temporal arteritis, we may see advances in treatment options to allow for a reduction in the use of high-dose systemic steroids.

Leonid Skorin Jr, DO, OD, MS, is an ophthalmologist at the Mayo Clinic Health System in Albert Lea, MN.

Paige Nash is a fourth year optometry student at Pacific University College of Optometry in Forest Grove, OR.

References:

- Nesher G. The diagnosis and classification of giant cell arteritis. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:73-75.

- Salvarani C, Cantini F, Boiardi L, Hunder GG. Medical progress: polymyalgia rheumatica and giant-cell arteritis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(4):261-271.

- Charlton R. Optimal management of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2012;8:173-179.

- Hassan N, Dasgupta B, Barraclough K. Giant cell arteritis. BMJ. 2011;342:d3019.

- Behbehani R. Clinical approach to optic neuropathies. Clin Ophthalmol.2007;1(3):233-246.

- Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Arterial wall injury in giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(5):844-853.

- Chu E, Chen C. Concurrent central retinal artery occlusion and branch retinal vein occlusion in giant cell arteritis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:565-567.

- Walvick MD, Walvick MP. Giant cell arteritis: laboratory predictors of a positive temporal artery biopsy. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(6):1201-1204.

- Hunder G, Bloch D, Michel B, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1122-1128.

- Murchison A, Gilbert M, Bilyk J, et al. Validity of the American College of Rheumatology criteria for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(4):722-729.

- Hoffman G, Cid M, Hellmann D, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of adjuvant methotrexate treatment for giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(5):1309-1318.

- Gunawardene A, Chant H. Facial nerve injury during temporal artery biopsy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96(4):257-260.

- Niederkohr RD, Levin LA. A Bayesian analysis of the true sensitivity of a temporal artery biopsy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(2):675-680.

- Luqmani R. Treatment of polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis: are we any further forward? Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:674-676.

- Yates M, Loke YK, Watts RA, MacGregor AJ. Prednisolone combined with adjunctive immunosuppression is not superior to prednisolone alone in terms of efficacy and safety in giant cell arteritis: meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33(2):227-236.