Severe Dysphagia from Medication-Induced Esophagitis: A Preventable Disorder

Dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, is a common medical problem that has many causes, including esophageal injury.1-8 Currently, more than 70 frequently used medications have been implicated in esophageal injury, and medication-induced esophagitis (also known as “pill-induced esophagitis”) should be considered in the differential diagnosis of dysphagia in individuals who take prescription and over-the-counter medications. Yet this etiological factor regularly escapes detection or goes unrecognized. As a result, dysphagia in patients with medication-induced esophagitis is often managed inappropriately.

In older adults, swallowing problems may be automatically attributed to such common causes as stroke or dementia. Secondary causes like pill-induced esophageal injury are never considered. Further, some patients—such as those with dementia who can no longer feed themselves—are fitted with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes (PEGs) or surgically placed gastrostomies and subjected to these parenteral feeding approaches for the rest of their lives without ever having received a proper evaluation for dysphagia. The potential for reversing dysphagia in these patients and improving oral feeding is seldom considered.

We present the case of a community-dwelling older adult who presented with severe dysphagia and required placement of a gastrostomy tube (G-tube) for long-term nutritional support. During follow-up, the ambulatory geriatrics clinic continued to look for and identified the etiology of her dysphagia as medication-induced esophagitis. Months after the appropriate corrective measures were taken, the feeding tube was removed and the patient was able to resume normal feeding. Following the case presentation, we review steps for detecting and managing dysphagia arising from medication-induced esophagitis.

Case Presentation

An 86-year-old white woman was admitted to the acute care geriatric unit of our teaching hospital because of severe dysphagia. She could not swallow anything, including sips of water, and also presented with excessive salivation and dyspnea. The dysphagia had worsened gradually over the past several weeks and was associated with weight loss.

The patient was a past smoker and denied alcohol use. Her comorbidities included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, anemia, and vitamin B12 deficiency. She required some assistance to perform her activities of daily living (ADLs) and her instrumental ADLs. Her mobility was limited, as evidenced by a pressure ulcer. Medication use consisted of aspirin 81 mg once daily, simvastatin 20 mg once daily, lisinopril 5 mg once daily, and ferrous sulfate 325 mg once daily.

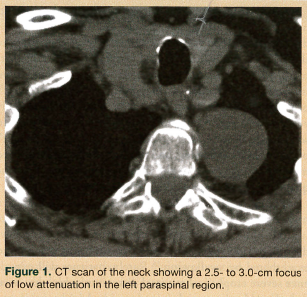

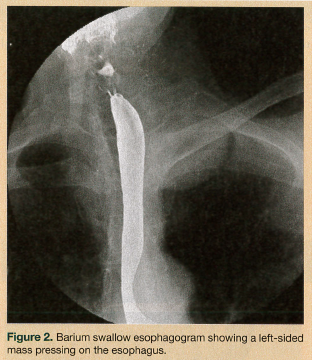

On physical examination, the patient had a body mass index of 22.4. She was hemodynamically stable and well oriented, with no evidence of neurological deficit. Her oropharynx was clear and her uvula was erythematous. Saliva drooled from the angle of mouth, with no clinical suggestion of aspiration. An attempted upper esophageal endoscopy revealed obstruction of the upper esophagus and blackish discoloration of the esophageal mucosa, and it could not be completed. A chest radiograph and electrocardiogram were unremarkable. Fiberoptic laryngoscopy ruled out an upper airway lesion, but showed posterior glottic edema. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the neck and chest added to the confusion, showing a soft-tissue density surrounding the proximal esophagus and a possible 2.5-cm homogenous attenuated paraspinal density (most likely a nerve sheath tumor) in the left upper lobe (Figure 1). A barium swallow esophagram was performed, which showed the esophagus being compressed by the mass (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s head and neck revealed a circumferential mass lesion around the proximal esophagus and a left paraspinal round, well-circumscribed area representing a mass or complex cyst.

On physical examination, the patient had a body mass index of 22.4. She was hemodynamically stable and well oriented, with no evidence of neurological deficit. Her oropharynx was clear and her uvula was erythematous. Saliva drooled from the angle of mouth, with no clinical suggestion of aspiration. An attempted upper esophageal endoscopy revealed obstruction of the upper esophagus and blackish discoloration of the esophageal mucosa, and it could not be completed. A chest radiograph and electrocardiogram were unremarkable. Fiberoptic laryngoscopy ruled out an upper airway lesion, but showed posterior glottic edema. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the neck and chest added to the confusion, showing a soft-tissue density surrounding the proximal esophagus and a possible 2.5-cm homogenous attenuated paraspinal density (most likely a nerve sheath tumor) in the left upper lobe (Figure 1). A barium swallow esophagram was performed, which showed the esophagus being compressed by the mass (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s head and neck revealed a circumferential mass lesion around the proximal esophagus and a left paraspinal round, well-circumscribed area representing a mass or complex cyst.

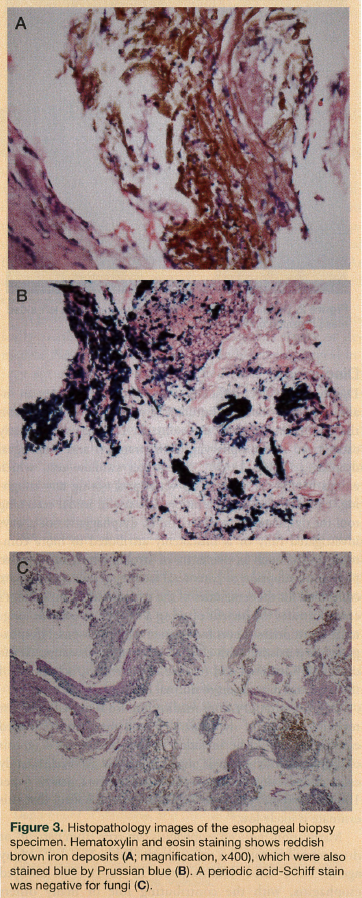

On the fifth day after hospital admission, a G-tube was surgically placed to provide the patient with nutritional support. Another upper endoscopy was attempted on day 8, but an obstruction again prevented the scope from advancing beyond the sphincter. Biopsied tissue from the site of obstruction revealed only a few fragments of squamous epithelium with acute inflammation and reactive atypia; fragments of inflamed, ulcerated granulation tissue with crystalline foreign material; and necrotic tissue. Periodic acid-Schiff staining demonstrated no fungal organisms.

CT scanning of the neck and chest was repeated 3 weeks after admission. The images depicted the same abnormalities as before, but they appeared less prominent. Upper endoscopy was attempted again and was successful this time, revealing grade I reflux esophagitis and possible extrinsic compression at the upper esophageal sphincter, but no intrinsic mass. The gastroesophageal junction was normal, as were the stomach, pylorus, and duodenum. A barium swallow was performed that same day and revealed no abnormalities. A speech and swallow evaluation confirmed that the patient was now able to swallow foods with pureed and thin-liquid consistencies, and the patient was discharged to home.

CT scanning of the neck and chest was repeated 3 weeks after admission. The images depicted the same abnormalities as before, but they appeared less prominent. Upper endoscopy was attempted again and was successful this time, revealing grade I reflux esophagitis and possible extrinsic compression at the upper esophageal sphincter, but no intrinsic mass. The gastroesophageal junction was normal, as were the stomach, pylorus, and duodenum. A barium swallow was performed that same day and revealed no abnormalities. A speech and swallow evaluation confirmed that the patient was now able to swallow foods with pureed and thin-liquid consistencies, and the patient was discharged to home.

Three months after the patient was discharged from the hospital, with the feeding tube still in place, a modified barium swallow study with video fluoroscopic examination demonstrated out-pouching at the posterior wall of the esophagus, but ruled out any risk of aspiration associated with any food consistency. Biopsied tissue of the esophagus obtained during endoscopy revealed stains negative for fungi but positive for rusty brown iron, confirming a diagnosis of pill-induced esophagitis secondary to ferrous sulfate (Figure 3). Although ferrous sulfate was the most prominent cause of the patient’s medication-induced esophagitis, other pills likely contributed. Six months after the patient was originally hospitalized, her feeding tube was removed. The patient returned to her normal self, regained the weight she had lost, and was again enjoying life and her favorite foods.

Discussion

Dysphagia involves difficulty swallowing and denotes an inability to pass foods or liquids easily from the mouth down the esophagus to reach the stomach. Dysphagia is broadly categorized into oropharyngeal (or transfer) and esophageal dysphagia (Table 1).2-4,9,10 The water swallow test, which entails having the patient sip water and noting any coughing, choking, or voice alteration, is a useful initial screening tool for dysphagia.11 In older adults, dysphagia is not always investigated fully or is mistakenly attributed to more common causes, such as dementia or stroke, which can lead to premature adoption of parenteral feeding approaches that are continued for the remainder of the patient’s life. Our patient’s case illustrates the benefit of using a G-tube to provide long-term nutritional support for a patient with new-onset dysphagia while persisting with efforts to determine its causes. If the causes are identified and reversible, the reward is removal of the tube and restoration of normal feeding.

Esophageal injury from medication use is one of the most reversible causes of dyphagia,4,12-18 and medication-induced esophagitis should be included in the differential diagnosis of dysphagia, odynophagia, and esophagitis. A Swedish study estimated the incidence of pill esophagitis at nearly 4 per 100,000 patients per year, with the authors noting that this estimate is likely low.19

Medication-induced esophagitis can arise from patient- or drug-related factors or a mix of both (Table 2).1,3,4,12-15 Many agents have been incriminated in medication-induced esophagitis, with the contributing role of many others likely underrecognized and underreported.1,4,9,13-18 Antibiotics account for half the reports of pill-induced esophagitis (Table 3).16 The acidic (eg, ascorbic acid, ferrous sulfate) or alkaline (eg, alendronate) properties of a drug, its hyperosmolar state (eg, potassium chloride solution), or direct toxicity level (eg, tetracycline) may all contribute to the risk of medication-induced esophagitis.20-22 Polypharmacy, which is prevalent among the geriatric population, increases the potential for inappropriate medication use23 or drug-drug interactions and leaves older adults especially vulnerable to developing medication-induced esophagitis. In some cases, however, the specific agent taken, the patient’s posture while swallowing, and the amount of water ingested may contribute more to the likelihood of injury than the quantity of medications taken.16

Medication-induced esophagitis can arise from patient- or drug-related factors or a mix of both (Table 2).1,3,4,12-15 Many agents have been incriminated in medication-induced esophagitis, with the contributing role of many others likely underrecognized and underreported.1,4,9,13-18 Antibiotics account for half the reports of pill-induced esophagitis (Table 3).16 The acidic (eg, ascorbic acid, ferrous sulfate) or alkaline (eg, alendronate) properties of a drug, its hyperosmolar state (eg, potassium chloride solution), or direct toxicity level (eg, tetracycline) may all contribute to the risk of medication-induced esophagitis.20-22 Polypharmacy, which is prevalent among the geriatric population, increases the potential for inappropriate medication use23 or drug-drug interactions and leaves older adults especially vulnerable to developing medication-induced esophagitis. In some cases, however, the specific agent taken, the patient’s posture while swallowing, and the amount of water ingested may contribute more to the likelihood of injury than the quantity of medications taken.16

Making a timely diagnosis requires maintaining a high index of clinical suspicion. In patients experiencing pill-induced esophagitis, chest pain typically follows drug ingestion; the pain can be continuous, severe, and exacerbated by swallowing.16 Rarely, patients will experience severe esophageal mucosal dissection, which has been linked to bleeding tendencies associated with anticoagulant therapy.24 Appropriate questions must be asked to elicit pertinent details about drugs used and how they are taken. The drug history should be meticulous and include all prescribed and over-the-counter medications used and their dosing regimens. Patients should be asked about their position while taking medications (eg, standing, lying down, sitting), how much water or other liquids they ingest with their drugs, the proximity of doses to mealtimes, and whether pills are taken whole or if they are first split or crushed.

Making a timely diagnosis requires maintaining a high index of clinical suspicion. In patients experiencing pill-induced esophagitis, chest pain typically follows drug ingestion; the pain can be continuous, severe, and exacerbated by swallowing.16 Rarely, patients will experience severe esophageal mucosal dissection, which has been linked to bleeding tendencies associated with anticoagulant therapy.24 Appropriate questions must be asked to elicit pertinent details about drugs used and how they are taken. The drug history should be meticulous and include all prescribed and over-the-counter medications used and their dosing regimens. Patients should be asked about their position while taking medications (eg, standing, lying down, sitting), how much water or other liquids they ingest with their drugs, the proximity of doses to mealtimes, and whether pills are taken whole or if they are first split or crushed.

Theoretically, even if the patient’s history and presentation are atypical, upper endoscopy should help confirm a diagnosis of medication-induced esophagitis.1,12 Pill-induced injuries are observed primarily in the mid-third of the esophagus and generally consist of erosions, kissing ulcers (when a pair of ulcers come into contact with one another), and several small bleeding ulcerations.4 Another possible finding in a patient with dysphagia, as was the case with our patient, is iron deposits in the upper gastrointestinal tract. These deposits are more frequently observed in patients taking iron supplements and can harm the esophageal and gastric mucosa. One study reported that 86% of patients who had esophageal iron deposits also had erosions associated with the deposits.20,21

Dysphagia lusoria is a rare anomaly that predisposes affected patients to pill-induced esophagitis.25 The term lusoria is derived from the Latin term lusus naturae and literally translates to “freak of nature.” Patients with dysphagia lusoria typically have a right-sided aortic arch with an aberrant right subclavian artery placing extrinsic pressure on the esophagus.26 CT scanning and MRI of the chest can confirm the presence of a right-sided aortic arch and proximal esophageal dilatation, which is where medications get lodged.25

Once a diagnosis of medication-induced esophagitis is confirmed, supportive care, patient education, and adjunctive therapy should be instituted. Patients with acute medication-induced esophageal injury may benefit from avoiding an implicated drug or drugs and any foods or drinks, such as alcohol, that might irritate the injury. Sucralfate, which works by coating, protecting, and promoting healing of ulcerated esophageal mucosa, can also be administered.14,15 On rare occasions, patients with severe odynophagia may require temporary parenteral feeding. If the medication-related injury results in an esophageal stricture, which has been observed with calcium multimineral formulations, dilatation may be needed.27

Once the acute phase of dysphagia has resolved, the entire medication list must be reviewed to determine whether suspected offending agents should be discontinued or switched. For example, alendronate is associated with chemical esophagitis, and discontinuation may be warranted to ensure recovery.28,29 It may be possible to substitute some agents with other formulations, such as crushed or liquid preparations, that reduce the duration of contact between the drug and the esophageal mucosa. If it is not in the patient’s best interest to discontinue or switch an implicated drug, the patient should be instructed on how to minimize the risk of injury when taking the medication.1,12,14,15

Although severe medication-induced esophagitis is sometimes reversible, feeding tube placement to provide long-term nutritional support may be necessary if food fails to pass through the esophagus and oral feeding is not possible. A G-tube is indicated for patients with mechanical esophageal blockage, just as it is for patients who have esophageal cancer or strictures from an inflammatory or caustic injury.30 Our patient’s medication-induced injuries resulted in a mechanical blockage that left her unable to eat or drink, requiring use of a G-tube. When a feeding tube is placed, efforts should continue to address potential correctable factors and enable removal of the feeding tube and resumption of normal feeding.

It is common to place PEGs in patients with advanced dementia despite recent evidence that suggests they do not improve quality of life, reduce aspiration risk, improve healing of pressure ulcers, or prolong survival.31-35 Studies indicate that when asked, most patients express a preference for oral feeding over PEG.34 Mortality following PEG placements remains high, although it may be possible to predict mortality risk using Charlson’s comorbidity index (a higher score correlates with higher mortality risk) and C-reactive protein values.35 Physicians and caregivers should allow quality-of-life issues, ethical considerations, patient preferences, and contextual features to guide them when deciding on a method of nutritional support.36 Our patient had severe dysphagia accompanied by weight loss, which is why we decided to use long-term G-tube feeding. We continued to pursue the etiology of her dysphagia, leading to a diagnosis of

medication-induced esophagitis. In this case, the condition was completely reversible, ultimately allowing elective removal of the G-tube.

Once medication-induced esophagitis has been resolved, preventing recurrence is always preferred over retreatment and entails educating patients on how to ingest their medications appropriately.1,12,14,15 Ideally, medications should be swallowed with at least 8 oz of water. Most drugs should be taken while standing or seated upright and patients should generally be advised against lying flat immediately after ingestion. With some medications, such as bisphosphonates, waiting at least 30 minutes after ingestion helps ensure optimal absorption. H2-receptor blockers or proton pump inhibitors, which suppress acid, can be administered in some cases. When gastroesophageal reflux disease is suspected as a contributing factor, it may be useful to prescribe sucralfate, which coats and protects the esophageal mucosa.14,15

Effective prevention of medication-induced esophagitis is similar to preventing recurrence and requires healthcare providers to be aware of the risks and to provide clear instructions to their patients on the principles of proper drug administration. It is important to ensure that patients fully comprehend and follow these instructions. In patients with left atrial enlargement, the enlarged left atrium may exert external compression over the distal esophagus and care should be taken when using medications that predispose individuals to esophagitis.37,38

Conclusion

Much can be done to prevent pill- or medication-induced esophagitis.13 Pharmacists, nurses, and physicians can play a pivotal role by being proactive in identifying circumstances that predispose patients to drug-induced injuries and dysphagia.9 The disorder has drawn the attention of manufacturers, who we hope will design future pills with the intent of reducing the risk of complications during ingestion and transit. Already, greater awareness of the condition in conjunction with preventive approaches have helped decrease the incidence of medication-induced esophagitis.16 As awareness continues to grow, especially among medical professionals who care for geriatric patients, more patients with dysphagia due to medication-induced esophagitis stand to receive appropriate diagnosis and management.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Jaspersen D. Drug-induced esophageal disorders: pathogenesis, incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22(3):237-249.

2. White GN, O’Rourke F, Ong BS, Cordato DJ, Chan DK. Dysphagia: causes, assessment, treatment, and management. Geriatrics. 2008;63(5):15-20.

3. Lind CD. Dysphagia: evaluation and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32(2):553-575.

4. Abid S, Mumtaz K, Jafri W, et al. Pill-induced esophageal injury: endoscopic features and clinical outcomes. Endoscopy. 2005;37(8):740-744.

5. Cefalu CA. Appropriate dysphagia evaluation and management of the nursing home patient with dementia. Ann Longterm Care. 1999;7(12):447-451.

6. Aparanji KP, Dharmarajan TS. Pause before a PEG: a feeding tube may not be needed in every candidate. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2010;11(6):453-456.

7. Dharmarajan TS, Polavarapu V. “Double dysphagia” in an older female. Pract Gastroenterol. 2004;28(9):60-64.

8. Jayadevan R, Pitchumoni CS, Dharmarajan TS. Dysphagia in the elderly. Pract Gastroenterol. 2001;25(9):75-82,88.

9. O’Neill JL, Remington TL. Drug-induced esophageal injuries and dysphagia. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(11):1675-1684.

10. Lawal A, Shaker R. Esophageal dysphagia. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2008;19(4):729-745

11. Suiter DM, Leder SB. Clinical utility of the 3-ounce water swallow test. Dysphagia. 2008;23(3):244-250.

12. Arora AS, Murray JA. Iatrogenic esophagitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2000;2(3):224-229.

13. Geagea A, Cellier C. Scope of drug-induced, infectious and allergic esophageal injury. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24(4):496-501.

14. Winstead NS, Bulat R. Pill esophagitis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2004;

7(1):71-76.

15. Vãlean S, Petrescu M, Cãtinean A, Chira R, Mircea PA. Pill esophagitis. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14(2):159-163.

16. Kikendall JW. Pill-induced esophagitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;3(4):275-276.

17. Emami MH, Haghighi M, Esmaeili A. Esophagitis caused by ciprofloxacin: a case report and review of the literature. Govaresh. 2004;9(4):272-276.

18. Kadayifici A, Gulsen MT, Koruk M, Savas MC. Doxycycline-induced pill esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2004;17(2):168-171.

19. Carlborg B, Kumlien A, Olsson H. Drug-induced esophageal strictures [in Swedish]. Lakartidningen. 1978;75(49):4609-4611.

20. Kaye P, Abdulla K, Wood J, et al. Iron-induced mucosal pathology of the upper gastrointestinal tract: a common finding in patients on oral iron therapy. Histopathology. 2008;53(3):311-317.

21. Chen Z, Scudiere JR, Montgomery E. Medication-induced upper gastrointestinal tract injury. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62(2):113-119.

22. Katzka DA. Esophageal disorders caused by medications, trauma and infection. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology/Diagnosis/Management. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2006:937-948.

23. Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts [published correction appears in Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(3):298]. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2716-2724.

24. Adachi W, Watnabe H, Yazawa K, et al. A case of pill-induced esophagitis with mucosal dissection. Diagn Ther Endosc. 1998;4(3):149-152.

25. Malhotra A, Kottam RD, Spira RS. Dysphagia lusoria presenting with pill induced oesophagitis: a case report with review of literature. BJMP. 2010;3(2):312.

26. Bickston S, Guarino P, Chowdhry S. Education and imaging. Gastrointestinal: dysphagia lusoria. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(6):989.

27. Wardlaw R, Victor D, Fergans J, Smith J. Calcium multi-mineral complex induced esophageal stricture. Ochsner J. 2007;7(3):125-128.

28. Zografos GN, Georgiadou D, Thomas D, Kaltsas G, Digalakis M. Drug-induced esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22(8):633-637.

29. Tóth E, Fork FT, Lindelöw K, Lindström E, Verbaan H, Veress B. Alendronate-induced severe esophagitis. A rare and severe reversible side-effect illustrated by three case reports [in Swedish]. Lakartidningen. 1998;95(35):3676-3680.

30. Angus F, Burakoff R. The percutaneous endoscopic tube: medical and ethical issues in placement. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):272-277.

31. Naik AD, Abraham NS, Roche VM, Concato J. Predicting which patients can resume oral nutrition after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(9):1155-1161.

32. Callahan CM, Haag KM, Weinberger M, et al. Outcomes of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy among older adults in a community setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(9):1048-1054.

33. Dharmarajan TS, Unnikrishnan D, Pitchumoni CS. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and outcome in dementia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(9):2556-2563.

34. Skelly RH. Are we using percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy appropriately in the elderly? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2002;5(1):35-42.

35. Figueiredo FA, da Costa MC, Pelosi AD, Martins RN, Machado L, Francioni E. Predicting outcomes and complications of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Endoscopy. 2007;39(4):333-338.

36. Dharmarajan TS, Mathur S, Hudson A, Mansour L, Norkus EP. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in dementia: Areas for improvement in ethical aspects and documentation prior to the procedure. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2009;10(3):B12.

37. Lee RV, Freeman WA, Olson RJ. Dysphagia associated with left atrial enlargement and atrial fibrillation. Rocky Mt Med J. 1968;65(5):43-45.

38. Whitney B, Croxon R. Dysphagia caused by cardiac enlargement. Clin Radiol. 1972;23(2):147-152.