Toilet Training: How to Foster Success and Manage Pitfalls

ABSTRACT: The pediatric practitioner can play an essential role in support of families during the toilet training process. The 18-month visit is a good time to start discussing toilet training and the potential pitfalls. Early toilet training or training when a child or parent is not ready often contributes to complications. Child temperament can also affect training and should be considered. Constipation should be addressed first in all toilet training children, especially when training is difficult. Evaluation of constipation includes a thorough history and complete physical examination and often does not require invasive laboratory testing. In greater than 90% of cases of constipation, no organic cause is found, and treatment with laxatives is typically recommended. Chronic constipation or withholding can lead to encopresis. Treatment involves medication therapy to encourage softening and evacuation of stools and behavioral interventions focused on nonpunitive, reward-based incentives to develop mastery and confidence with the process and decrease anxiety. Parent education stresses the longstanding nature of treatment and that relapses can occur and sometimes a brief discontinuation of training is necessary. It is important to start with what a child can do and build on this concept to meet success. Regular follow-up is essential.

Toilet training is a major milestone in the lives of children and their parents. The process and potential pitfalls can also be a major source of stress. An understanding of the skills necessary for successful training and a proactive approach can help to decrease stress and assist parents in knowing what to do should the process go astray.

Here I discuss the fundamentals of successful toilet training and provide tips on how to identify and treat the major roadblocks to bowel and bladder continence. The focus will be on achieving and maintaining bowel continence. A discussion of urinary incontinence is beyond the scope of this article.

HOW TO FOSTER SUCCESS

When should toilet training be discussed?

Readiness for toilet training is based on developmental rather than chronological age. For children with typical development, the 18-month visit is a good time to start discussing what signs of readiness a child is showing. However, most children will start training later. If a child shows interest in the process by play or imitation, it may be a good time to introduce the concept of a potty chair. At 24 months, parents can introduce a step-by-step approach for teaching the child his or her role in the process. Most toileting readiness skills are not consolidated before this time.

The average age of daytime bladder and bowel training in the United States has increased over time; however, most neurotypical children in this country train by 3 years of age, with an average training time of 6 to 7 months.1 Because most children achieve daytime continence by 30 to 36 months, this is a good time to discuss any problems that may have arisen. Achieving nighttime continence is considered a separate process than daytime continence and nighttime wetting is considered normal until 6 years of age.

Is the child ready?

Readiness is the product of both physiologic and developmental maturation. Most of the physiologic and developmental skills necessary for toilet training begin around the age of 2 and are complete by 3 years of age. Some literature disputes the benefit of attempting toilet training before 27 months2 and notes increased time to train when earlier toilet training is attempted. However, no two children are alike when it comes to toilet training. Approaches and plans must take into consideration the unique needs of each child.

Physiologic skills. Certain physiologic signs of readiness should be present before training. These include:

•Voluntary bowel control (12 to 18 months).

•Awareness of urges (15 to 24 months).

•Ability to maintain dryness for at least 2 hours (26 to 29 months).

Developmental skills. The developmental readiness skills for training can be divided into multiple domains, including language, motor, and cognitive:

•Language signs involve the ability to follow commands and communicate steps in the process, such as the diaper being wet or soiled. The child needs to know how to imitate.

•From a motor standpoint, the child should be able to get to the bathroom and engage in tasks necessary for toileting, including removing clothing and sitting on the toilet. For children with physical disabilities, there may be other considerations.

•Cognitively, the child must understand what the potty is and what it is used for. Making this connection takes time. Attention is necessary to be able to spend adequate time to perceive an urge and then relax and release stool and/or urine.

Is there a lack of pathology?

Although not specifically a physiologic “sign,” one of the most important physiologic considerations is lack of pathology. Constipation is a major obstacle in toilet training for both day and night and must be addressed before the onset of training. Chronic distention of the colon affects bowel motor functioning and sensation and can hinder mastery of toilet training to stool. It can also cause irritation or compression of the bladder and affect urinary continence.

What factors may affect training?

Childhood development and timing play a large role in the toilet training process. The skills that are being learned and practiced by the toddler at this stage both assist in the toilet training process and contribute to some of the potential problems. The toddler has an intrinsic need to please and imitate parents, which is in some ways contradictory to his or her desire to maintain independence and autonomy. The child is also gaining self-awareness and becoming aware of the expectations of others. This can lead to conflict and subsequent anxiety.

Family pressures and stress also play a role in the timing and progression of toilet training. This might include a new sibling, new expectations at school, and other transitions. For children with physical or developmental disabilities, toilet training may need to be adjusted or special plans devised.

Some factors are known to be associated with the age of training:

•Gender: girls usually train earlier than boys by a few months.

•Birth order: younger siblings train more easily than first children (potentially secondary to the benefit of an experienced household).

•Race: non-Caucasians and children of single parents train earlier.3

Which method is best?

In the United States, there are different approaches to toilet training, and those in the mainstream have changed over time. Current popular practices are based on the influences of 2 main approaches:

•Child-directed approach, developed by Brazelton.4

•Parent-centered approach, popularized by Azrin and Foxx.5

The child-directed approach includes parent education and focuses on a child’s readiness cues, whereas the parent-centered method uses an operant conditioning model to teach a child this new skill. Although not compared head-to-head, both approaches are considered effective. The Brazelton method encourages child mastery on a step-by-step basis with the goal of decreasing stress within the family. The Azrin and Foxx method can also be effective in training children with disabilities.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ current recommendations for toilet training are based on the Brazelton method.6 Any toileting program must be built on what a child is already doing. The program must take into account the child’s temperament and personality. Parents should use a nonpunitive stepwise approach, and all caregivers need to be on the same page.

Successes need to be emphasized at each step using low-cost (stickers) and activity-based (fun time) rewards. However, it is important to change rewards over time in order to keep interest in this sometimes overwhelming process. High-cost incentives (eg, big presents, trips) may increase anxiety and provide only time-limited success. Assist parents in staying positive (this is often more challenging than one might think) and educate caregivers not to push a child who is resistant or who is not developmentally able.

HOW TO MANAGE PITFALLS

What is the clinician’s role in toilet training?

Clinicians can play a vital role in the toilet training process. They can serve as both a parental educator and an objective observer—who can direct some pressure away from the parents (ie, they can prescribe toileting “jobs” for the child). Early toilet training and training when a child or parent is not ready often contributes to toilet training problems. When addressed early enough, some toilet training issues can be managed easily with the treatment recommendations below. Practical tips for parents are summarized in the Parent Education Guide on page 315. The suggestions in the guide can be helpful for all children, including those for whom toilet training is difficult.

The mother of a 4-year-old boy asks for suggestions on toileting. She has tried several times over the past year and a half to train her son. Both the mother and father have tried to put him in “big boy pants.” They have given him incentives, like trips to Disney World, and have taken him to the bathroom every 30 minutes. The child is developmentally on track and has good vocabulary skills, but he is very resistant to toileting.

What are some toilet training complications?

Regression/resistance. Toileting regression refers to a situation in which a child is trained to stool and/or urine and then is no longer able or willing to do so. Toileting resistance refers to a conflict in the process itself in a child who is assumed to be ready.

Withholding. Withholding is the voluntary retention of urine or stool. A child who is resistant to toileting may withhold. Certain behaviors may be an indication of a withholding episode, including holding legs and buttocks stiffly together, rising on toes, rocking back and forth, and looking frozen during urge waves.

When a child withholds stool, it remains in the colon for longer periods. This results in greater water absorption and harder stools that are more painful to pass and that may increase withholding. Persistent stool withholding can lead to acute or chronic constipation and, in extreme cases, encopresis. Thus, quick recognition and management of withholding is essential.

What factors might lead to complications?

Some factors are known to contribute to “difficult toilet training,” of which the most common is the child’s temperament.7 Children who are less adaptable, who have more negative mood, and who are less persistent are more likely to have difficulties. Although these characteristics are intrinsic to the child, understanding them can be instrumental in moving the process along.

Constipation is one of the most important physiologic contributors to difficult toilet training. Every child needs to be evaluated for constipation both before consideration of toilet training and when difficulties arise. Treatment should be optimal and include close follow-up to ensure appropriate response to therapy.

Competing stressors, such as the start of school or a recent move, as well as other factors, such as trauma, organic pathology, developmental delays, parent mental health, maternal anxiety, and depression, may affect toilet training. Fear of the toilet and pain with defecation are other factors associated with toilet training complications.

What advice can be given to parents?

It is important to normalize temporary regression for parents. Because the timing of toilet training coincides with the struggle to gain autonomy, the process of toileting can often make a child feel out of control. When faced with a child who is either resistant or who has regressed, a major step is to help the child regain control. In some cases, parents may have to back off or discontinue toilet training temporarily. This may feel like a step backwards to parents. Helping them understand how this will meet the end goal is critical. It is also important to work with the parent to develop alternatives to the plan so that backing off does not feel stagnating (see the Parent Education Guide).

For the child who is withholding, parental education must include a discussion of the role of potential constipation and its prevention. Encouraging evacuation of stool through regularly scheduled toilet sitting with the use of a reward incentive plan can stop the cycle of withholding. Although not specifically discussed in the literature, performing Valsalva maneuvers (eg, use of blow toys, such as balloons, pinwheels, and kazoos) during sitting times may be helpful. For a child who is not yet constipated but is withholding, one might consider a low-dose stimulant laxative to make withholding more difficult.8

The parents of a 26-month-old girl are concerned that since they started toilet training, the child has begun to have hard, infrequent stools. They notice that she often stops what she is doing and rises up on her toes with a look of discomfort on her face.

What to look for in the evaluation of constipation?

Evaluation of constipation includes a thorough history with details, such as stool pattern and consistency. Use of the Bristol stool chart can be helpful (this can be downloaded for free from a variety

of online sources). Clinicians should perform a complete physical examination with focus on abdominal, neurological, and genitourinary findings.

A rectal examination is not always necessary, and in some cases can be performed at follow-up if symptoms persist after treatment. However, this examination should be performed by someone with experience in interpreting the findings.

Laboratory and diagnostic studies are rarely necessary and their use should be guided by the history and physical findings. It is important to look for anatomic, neurological, endocrine, and metabolic disorders. In more than 90% of cases of constipation, no organic cause is found.9

What to consider when treating constipation?

Constipation (either primary or secondary) needs to be treated aggressively. If no organic cause is suspected, treatment with laxatives is typically recommended. There are many treatment options and treatment choice is often guided by severity of symptoms, the child’s needs, and tolerance of adverse effects (eg, flatulence, cramping, and stool leakage) (Table 1). Clinicians must consider how the choice of treatment will affect the child’s functioning.

Although it is important to discuss fluid intake and diet, it is often difficult to make dietary changes sufficient to address more chronic constipation, especially in a child who has toileting concerns. Current data on the efficacy of dietary changes in treating constipation are not strong enough to support this as the sole treatment.10 Compliance with a high fiber diet is often poor because of adverse effects.

The family of a 6-year-old boy presents to clinic saying their child is still not toilet trained to stool. On further discussion, you determine that he began toilet training around 3 years of age, was briefly continent to stool for 6 to 8 months, and then began to have infrequent stools followed by stool incontinence. He is continent to urine for the most part.

What is encopresis?

Encopresis is the repeated passage of stool in places other than the toilet in a child older than 4 years. It can manifest as fully formed bowel movements, small accidents, or staining. The prevalence varies from 1.5% to 10%. Encopresis develops in about 3% of 4 year olds, 2% of 6 year olds, and 1.5% of 10 year olds, although it usually presents in children younger than 7 years.11 Boys are more likely than girls to have encopresis at a ratio of 6:1. As with withholding and regression/resistance, constipation plays a role in more than 90% of cases.12

In encopresis, retained stool results in dilation of the rectum.13 The bowel wall is stretched by the stool mass, and the rectum becomes impacted with hard feces. As water is absorbed by the gut wall, feces becomes harder the longer it remains in the colon. Stool accumulates and distention of the bowel occurs. The stretched muscles of the intestines lose their ability to contract effectively against the large mass, and nerve sensation in the rectum and anus is decreased. As large, harder stool is retained, newer, softer stool leaks around the hardened stool mass. Because of abnormal motor and neurological functioning, stool may be evacuated while the child is attempting to retain it. The child may also be unaware that an accident has occurred.

How is encopresis evaluated and treated?

Evaluation of encopresis is similar to that of constipation and includes a thorough history and physical examination with assessment for potential organic causes. In most cases, laboratory evaluations are unnecessary. Although a radiograph may not be needed to make the diagnosis, it can be a helpful adjunctive tool during the educational process (Figure). A radiograph can be used to demonstrate the large amount of retained stool, which can help parents understand the pathology. If an organic cause is suspected, referral to a gastroenterologist or other appropriate specialist is recommended.

Encopresis can be difficult to treat. Of patients with encopresis, 30% to 50% have resolution of symptoms (no or minimal soiling following the discontinuation of laxative treatment) after 1 year and 48% to 75% after 5 years.10,14 Management of encopresis involves 4 main components:

•Education.

•Bowel cleanout.

•Maintenance/rescue.

•Follow-up.

Education. Parents need to understand the physiologic component of encopresis and be made aware that this is a known disorder that is shared by other children. Many parents may not realize that much of what is occurring is involuntary. There may be blame involved. Parents often do not understand why the child is unaware of accidents or assume the child is lying. As part of understanding, they need to appreciate that nonpunitive approaches are essential to the process. This initial discussion can be both upsetting and a relief to parents.

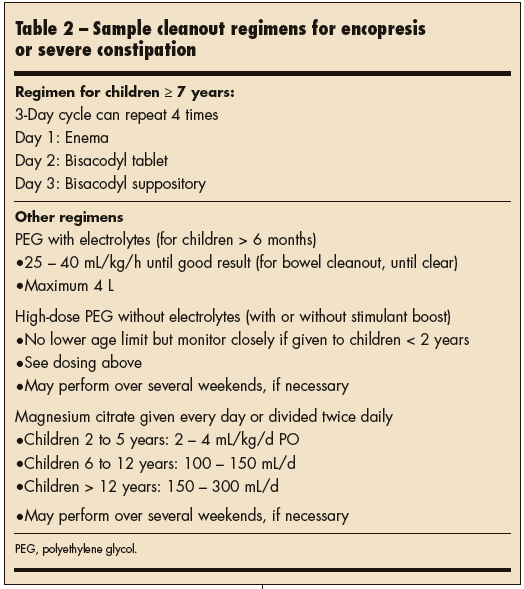

Bowel cleanout. A bowel cleanout is done in an effort to decrease distention and allow the bowel to begin the process of returning to its normal size and function—this may take 6 to 9 months. Potential cleanout regimens are listed in Table 2. Clinicians are encouraged to use a regimen with which they are comfortable and also works for the child and family. The regimens can be quick (take place over a weekend) or take longer depending on what works. A longer regimen might include 2 types of laxatives used together (ie, stimulant and osmotic). A shorter regimen may use higher doses of one laxative or different types of laxatives over several days in succession.

All regimens can be performed at home. Hospitalization is rarely necessary except in extreme cases. It is essential to follow up after cleanout to ensure efficacy of the regimen.

Maintenance/rescue. Once the bowel is cleaned out (which can typically be assessed by a thorough history and abdominal examination), the goal is to maintain regular bowel emptying and discourage reaccumulation of stool through a maintenance plan. Laxative therapy together with a behavioral program (see the Parent Education Guide) is most effective in demonstrating improvements.

Maintenance regimens should include an option that promotes regular, soft bowel movements (see Table 1). Polyethylene glycol without electrolytes is a good option because it is well tolerated at higher doses and can be titrated to effect. It can also be divided throughout the day. Magnesium hydroxide is also effective but compliance is often decreased because of taste. Mineral oil and lactulose are other options but can be accompanied by adverse effects, such as extra leakage and flatulence. Stimulant laxatives (bisacodyl, senna) can be given on weekends for added cleanout and in some cases are given daily in lower doses; however, because reliance on these medications may be a risk, continuous long-term use should be avoided.

There should also be a rescue plan in place should symptoms worsen. This includes temporarily increasing the laxative dose or performing another cleanout. In some cases, families are instructed to give a certain medication to the child if there are no bowel movements within a specified period.

Follow-up. Regular follow-up (after completion of initial cleanout and then at regular intervals depending on the needs of the family) is necessary to ensure consistency in treatment. Encourage families to return to the office as soon as a concern arises, which may mean coming in before a scheduled follow-up. It is important to inform parents that relapses are common and can occur during times of stress. Awareness ahead of time along with a predetermined rescue plan can decrease the negative impact of a regression on the patient and family.

Parent Education Guide

Convenient Hand-Outs on Important Health Issues

7 Tips for Troubleshooting Toilet Training

Despite everyone’s best efforts, there can be issues along the toilet training road. Here are 7 tips to help you navigate some of the potential obstacles and prevent complications.

1. Focus on what the child can do

Instead of focusing on what the child can’t or won’t do, start with what the child is able to do. Even for a child who has been a competent toileter, it may help to start at the beginning and break down toileting into small steps and reward each step. For instance, if a child is in pull-ups

or back in diapers, do diaper changes in the bathroom or have the child help with clean-up. The child may simply practice sitting on the toilet either with or without a diaper.

2. Eliminate stress around toilet training

Don’t push a child who is resistant or who is not developmentally able. For a child who is very resistant to toilet training or who is trained to stool and/or urine and then is no longer able or willing to do so (regression), consider backing off or discontinuing toilet training temporarily. This may feel like a step backwards. Having an alternative plan will help so that backing off does not feel stagnating. An example plan may be to stop training but involve the child in another reward incentive program, such as cleaning up toys. In 4 weeks, reintroduce toilet training.

3. Have scheduled sitting times

These should occur even if the child does not feel the urge to go (which he or she may not). To take advantage of the gastrocolic reflex, it is best to have the child sit about 30 minutes after meals. The sitting time should last about 10 minutes (shorter times can be considered in younger children).

4. Use a reward incentive plan

This should be used for sitting and usually consists of stickers or treats that can be turned in for a prize. The rewards should match the task. For instance, a child should not receive a new toy for sitting on the toilet. However, the child may earn the same toy through involvement in a regular program: the child may earn 1 sticker or treat for each scheduled sitting time; after the child earns X number of stickers, he or she receives a new toy, special activity, or event. Token rewards (stickers) for involvement should be provided directly after the child participates. High-cost rewards (big presents or trips) should be avoided.

5. Change rewards or prizes frequently

Given that toilet training can be a long process, it is essential to change rewards or prizes frequently to maintain motivation. Rewards should be adjusted depending on the child’s age. Visual systems, such as sticker or check charts, are helpful in keeping track of successes and prizes. Rewards should be given for effort in the process (ie, sitting on the toilet) not just for reaching a specific toilet training goal.

6. Consider other motivators

Keeping a special toy in the bathroom may be useful. While sitting on the toilet, the child can practice exercises that involve the Valsalva maneuver (blowing on a balloon or pinwheel). This can encourage stool evacuation.

7. Stay positive

Staying positive can be challenging even under the best of circumstances. You can take comfort in the fact that most children achieve daytime continence by 30 to 36 months of age. Be aware that certain medical conditions (eg, constipation) can complicate the toilet training process. It is important to seek help as soon as a concern arises, even if it is earlier than a regular scheduled visit. In children with constipation, relapses during the treatment process are common and can occur during times of stress.