Peer Reviewed

Umbilical Hernia

Authors:

Gerald Keller, DO

University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, Florida

Citation:

Keller G. Umbilical hernia. Consultant. 2017;57(6):377-378.

A 49-year-old man presented to establish care and to address his umbilical hernia (Figure 1), of which he desired surgical repair.

History. The patient had first noted the hernia 4 to 5 years prior, and it had steadily increased in size since then. It was not painful and had grown very slowly. He had been evaluated by a general surgeon approximately 3 years ago and had been scheduled to undergo surgical repair; however, he had cancelled the surgery the day before the operation due to anxiety about the procedure, and he had not seen a physician since then.

The patient had sustained a traumatic brain injury from a motor vehicle accident 30 years prior. The accident had left him physically disabled. He was a current smoker and drank 2 to 8 alcoholic beverages daily. Among his current medications were over-the-counter pain relievers, including acetaminophen and ibuprofen. He denied illicit drug use. He was monogamous with a female partner; however, the man had had multiple lifetime female partners.

Physical examination. A review of systems was positive for a rash on the patient’s chest, difficulty ambulating, and memory problems. He was 178 cm in height and weighed 89.8 kg (body mass index, 28.4 kg/m2). At presentation, his blood pressure was 142/92 mm Hg, his pulse was 101 beats/min, and his temperature was 36.8°C.

Physical examination revealed a man who appeared older than his stated age, sitting in a wheelchair, in no acute distress. Skin examination revealed a plaque consisting of numerous erythematous papules with overlying scale, measuring approximately 6 × 7 cm, over his central chest. He also had numerous tattoos.

Abdominal examination revealed a flat abdomen with normoactive bowel sounds. There was no obvious tenderness or guarding. The liver edge was palpable 2 cm below the costal margin, and the spleen tip was palpable. A 3.5-cm protruding mass with a slight bluish hue was present at the umbilicus. The mass was nontender and was soft and reducible. Light palpation of the mass revealed a light vibration/thrill, and auscultation of the mass revealed a constant harsh bruit.

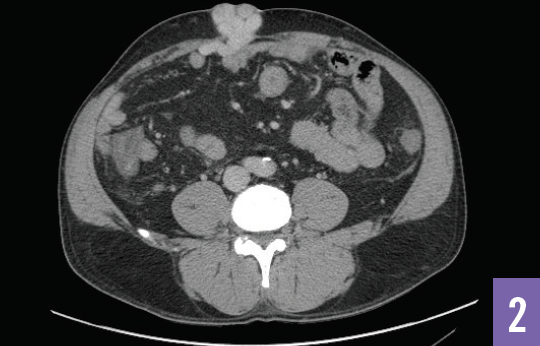

Diagnostic tests. The patient was sent for computed tomography angiography of the abdomen and pelvis, the results of which revealed a cirrhotic liver with an enlarged portal vein and splenomegaly with associated ascites. Additionally, there were markedly dilated varices from a recanalized paraumbilical vein at the umbilicus, causing the questionable mass/hernia (Figures 2 and 3).

Laboratory testing revealed an elevated total bilirubin level of 1.8 mg/dL and an elevated aspartate aminotransferase level of 67 U/L. The alanine aminotransferase level was normal. Hepatitis C antibody test results were positive, hepatitis B surface antigen test results were negative, and his international normalized ratio was 1.1. His platelet count was low at 72 × 103/µL.

Outcome of the case. The patient was referred to a hepatologist for further recommendations about treatment of his viral hepatitis C infection with cirrhosis and complications of portal hypertension. He also was referred to a gastroenterologist for evaluation of the paraumbilical varices. He was counseled to stop all over-the-counter pain relievers and to stop consuming alcoholic beverages.

Discussion. This patient’s case emphasizes the importance of a quality medical history and physical examination, especially if considering specialty or surgical consultation. Considering that this patient was not a woman and was not obese—both of which are factors known to increase the risk of umbilical hernia1—further investigation into possible underlying causes may have been considered prior to his referral.

Moreover, considering that up to 20% of patients with advanced liver disease develop umbilical hernias,1 often related to transmission of portal pressure via a recanalized umbilical vein,2 a thorough social history at the patient’s initial presentation to a general surgeon 3 years previously may have led to a more timely diagnosis and treatment of this patient’s severe liver disease. His initial abdominal examination should have included light palpation, which may have revealed a thrill over the hernia and therefore clued in the examining physician to the patient’s underlying disease process.

Finally, this patient had been previously scheduled for operative repair of a suspected simple umbilical hernia based upon clinical examination findings alone; if the patient had not cancelled the procedure, he may have had life-threatening bleeding from his undiagnosed paraumbilical varices.

This case also demonstrates the need for further research regarding the herniation of vascular tissue in the setting of portal hypertension. Compared with conservative management, elective umbilical hernia repair has been shown to reduce the risk of incarceration-related mortality in cirrhotic patients.3 Unfortunately, surgical repair in this patient’s case would likely involve ligation of the patent umbilical vein, which has been shown to cause acute portal vein thrombosis and subsequent acute liver failure.3 Considering that the patient is not a liver transplant candidate as a result of his continued consumption of alcohol, it would be beneficial to know whether an attempted repair would increase or decrease his mortality risk compared with conservative management.

REFERENCES:

- McAlister V. Management of umbilical hernia in patients with advanced liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2003;9(6):623-625.

- Shlomovitz E, Quan D, Etemad-Rezai R, McAlister VC. Association of recanalization of the left umbilical vein with umbilical hernia in patients with liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2005;11(10):1298-1299.

- Eker HH, van Ramshorst GH, de Goede B, et al. A prospective study on elective umbilical hernia repair in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites. Surgery. 2011;150(3):542-546.