Peer Reviewed

Vocal Cord Dysfunction: A Pernicious Pitfall in Asthma Diagnosis and Treatment

Authors:

Ernest Pierce Stewart, DO; Claudia M. Vukovich, RCP, RRT, AE-C, CCM; and Samuel Louie, MD

Citation:

Stewart EP, Vukovich CM, Louie S. Vocal cord dysfunction: a pernicious pitfall in asthma diagnosis and treatment. Consultant. 2018;58(5):e174.

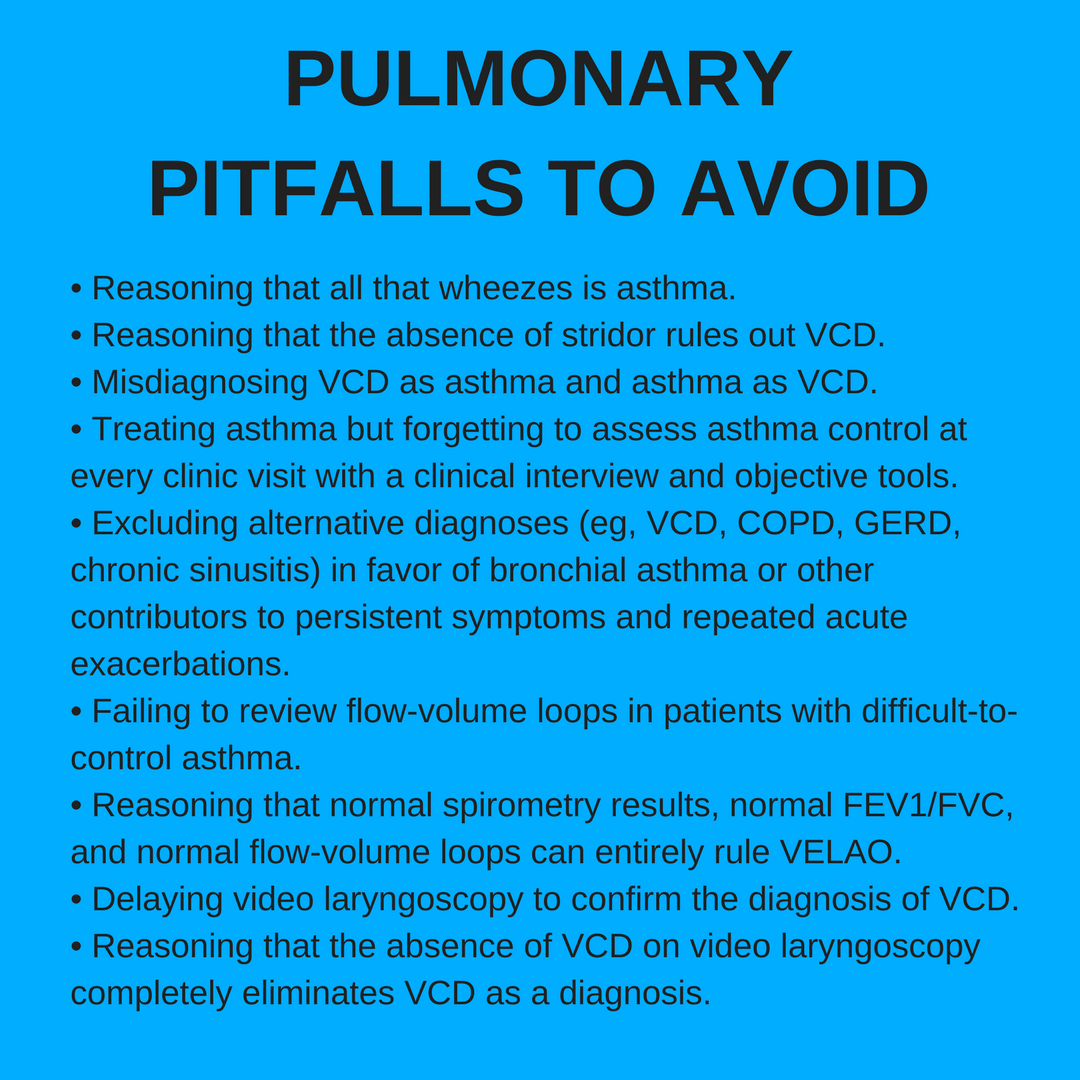

The old adage, “Not all that wheezes is asthma,” attributed to physician Chevalier Jackson (1865-1958), has never been more relevant than today, given reports that at least 30% of physicians’ asthma diagnoses are incorrect (Table 1).1 Very few patients are completely resistant to or refractory to treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) or combination ICS and long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) drug therapy. When patients are unresponsive after approximately 3 months of ICS-LABA therapy, severe asthma may be present.

The overdiagnosis of allergic or nonallergic asthma can lead to weeks, months, or even years of unnecessary albuterol and controller drug treatment, exposing patients to the risks of prolonged drug therapies such as pneumonia, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and/or Cushing syndrome.

The overdiagnosis of severe asthma, as recently defined by GINA in 20182 and by the European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society in 2014,3 could expose patients to advanced asthma biologic therapies and even procedures (eg, bronchial thermoplasty). While these treatments have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to help control symptoms and reduce exacerbations in difficult-to-control asthma, these patients must actually have asthma to benefit from these treatments. Thus, they must undergo clinical evaluation to confirm the diagnosis of asthma again, to identify comorbidities, and to check inhaler techniques, medication adherence, and exposure to tobacco smoke, air pollution, or allergens.

Patient safety is endangered when clinicians hurry to the incorrect diagnosis of asthma or fail to fully understand why a patient continues to have uncontrollable symptoms assessed clinically and by the Asthma Control Test for more than 3 to 6 months despite patient education and adherence to a written asthma action plan with asthma controller drugs.

Establishing a correct diagnosis of asthma cannot rely on the detection of symptoms alone, because the symptoms of wheezing, cough, and dyspnea on exertion are all nonspecific. Furthermore, pulmonary function test results are often normal in asthma and thus cannot distinguish between asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) when they are abnormal.

Asthma, COPD, and ACOS all display obstructive patterns on spirometry, and most cases are responsive to bronchodilators (eg, albuterol), thus overturning the old dogma that asthma is “reversible” but COPD is “irreversible.” Completely or partially reversible airflow obstruction with pre- and post-bronchodilator improvement in forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration (FEV1) after albuterol treatment (at least 15% reversibility or responsiveness, or at least 12% reversibility and a 200-mL improvement in forced vital capacity [FVC]) cannot eliminate COPD or ACOS.

Another important pitfall to avoid is to diagnose asthma before all reasonable alternative diagnoses have been excluded. One of the most common disorders that frequently escape early diagnosis is vocal cord dysfunction (VCD), which requires clinicians to assess a patient’s difficulty in taking in a breath as well as expelling air out of the lungs.

NEXT: Clinical Manifestations

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

VCD describes inappropriate or paradoxical vocal fold movement (the vocal cords actually move with the folds) on inspiration much more so than on expiration. There is an involuntary loss of neuromuscular control of the vocal cords and aryepiglottic folds in the larynx. Inaccurate terms used to describe VCD in the medical literature include psychogenic stridor, factitious asthma, and Munchausen stridor.4-6

VCD can occur in children and adults. Patients are most often misdiagnosed with severe asthma for months or even years. Many patients report a recent upper respiratory tract infection and the subsequent development of “asthma” that is very difficult to control, despite GINA guideline–recommended drug treatments, including ICS-LABA with or without prednisone.

Common VCD symptoms such as stridor and throat tightness can manifest in patients without asthma as sudden upper airway obstruction. It is imperative not to miss pulmonary aspiration, angioedema, foreign body aspiration, pharyngeal abscess, or even epiglottitis in adults. These conditions can be life-threatening and often can be differentiated from VCD by clinical history and physical examination.

VCD can present in patients with asthma and is much more common in patients with difficult-to-control asthma than is generally appreciated. The literature cites a VCD prevalence of 5% in persons with severe asthma, but it can range as high as 40%.4-7 Our experience at UC Davis is 10% to 15% in persons with severe asthma, but we suspect that many cases escape diagnosis, given that the triggers are myriad (Table 2). We suspect that VCD is an unrecognized cause of acute exacerbations of COPD, particularly when there is no evidence of infection or when dyspnea cannot be attributed to pulmonary aspiration, nonadherence to the COPD action plan, or pulmonary embolism.

The medical history of the patient can be very helpful. Patients with VCD have more problems breathing air into the lungs and may report throat tightness and symptoms of choking. It is a major pitfall to think that the absence of inspiratory (or expiratory) stridor in a patient’s clinical history or during a clinic or emergency department visit rules out VCD.

VOCAL CORD DYSFUNCTION INDEX

The Pittsburgh Vocal Cord Dysfunction Index is simple to use in the clinic and can lead to the definitive diagnosis of VCD.8 A score of 4 or greater has a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 95% for the diagnosis of VCD (Table 3).

NEXT: Flow-Volume Loops

FLOW-VOLUME LOOPS

Variable extrathoracic large airway obstruction (VELAO) can be detected via auscultation of the neck during inspiration and of the chest during exhalation. The wheezing will sound very distant with chest auscultation and very loud over the neck. Further immediate investigation for VCD can be done during a clinic visit with simple spirometry by evaluating flow-volume loops (Figures 1-3).9

Figure 1: A normal flow-volume loop. Note that the inspiratory limb of the graph resembles the bottom of a chicken’s egg.

Figure 2: Comparison of flow-volume loops and their clinical implications.

Figure 3: Examples of VELAO first detected by flow-volume loops using office spirometry. 3A, 3B, and 3D-3F, patients with both asthma and confirmed VCD; 3C, a patient with both COPD and confirmed VCD.

Spirometry results and both FEV1/FVC and FEV1 are often normal (>0.80 and >80% predicted, respectively) in VCD cases, which is an important clue that the patient’s physiology is not entirely consistent with the diagnosis of severe asthma where FEV1/FVC is often 0.70.

In our experience at UC Davis, the classic truncated or flattened inspiratory flow limb of the flow-volume loop is fixed or appears repeatedly on flow-volume loops in approximately 25% of cases. Most VELAO cases go undetected, because clinical practice focuses on the expiratory flow limb of the flow-volume loops. VELAO is intermittent, and its presence can easily elude even experienced clinicians and thus requires a high index of suspicion.

The flow-volume loop is more often normal in appearance without evidence of VELAO between VCD events, but the outward signs and symptoms can mimic asthma attacks or flares. It is important to examine all of the flow volume loops for VELAO when they are available given the sporadic or episodic nature of VCD.

Evidence of VELAO on the inspiratory limbs of the flow-volume loops from office spirometry can provide the best early clues for VCD. These patients may report having problems inhaling and exhaling air from their lungs. Choking, a sense of throat tightness (rather than chest tightness), and changes in voice are all nonspecific symptoms. The definitive diagnosis requires video laryngoscopy.4-7

In their classic review, Newman and colleagues6 retrospectively analyzed the demographic, historical, laboratory, and psychiatric characteristics of 95 hospitalized patients with laryngoscopy-confirmed VCD, 53 of whom also had asthma. Most of the 42 patients with VCD but not asthma were women aged 35 to 40 years, many of whom worked in health care. The authors found that the patients with VCD but without asthma had been misdiagnosed as having asthma for a mean of 4.8 years; 34 of the 42 patients had been receiving an average daily prednisone dose of 29.2 mg before the correct diagnosis was made. These patients demanded extraordinary urgent-care resources, including a mean of 10 emergency department visits and 6 hospitalizations annually. A stunning 28% of the patients with VCD but without asthma had been intubated for apparent acute respiratory failure.

The lesson here is to consider VCD in every case of presumed asthma, particularly if the symptoms are difficult to control. Ask patients whether they have more difficulty breathing air into their lungs or out of their lungs. The former should alert the clinician to the possibility of VELAO, which can result from conditions other than asthma with or without VCD (eg, laryngeal diseases including cancer, sarcoidosis, lymphoma, or goiter).

At UC Davis, we promote office spirometry in primary care and specialty clinics and encourage careful review of the inspiratory limb of the flow-volume loops, which can provide immediate and valuable evidence of inspiratory airway flow obstruction that is possibly a result of VCD, in addition to the expected expiratory airway flow obstruction associated with severe asthma.

NEXT: VCD Diagnosis

VCD DIAGNOSIS

The vocal cords are appropriately abducted (ie, move left and right) throughout the respiratory cycle in normal individuals. It is normal for the vocal folds to abduct (>50%) during inspiration and narrow slightly during passive expiration. Vocal cords may be normally adducted (ie, come together and may touch) at the end of expiration (not inspiration) during FVC maneuvers. Voice and speech require the vocal folds and cords to approximate one another and vibrate during expiration.

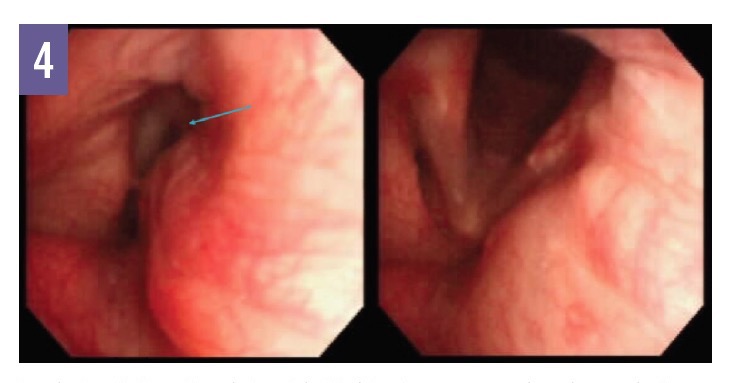

In VCD, vocal fold and vocal cords adduct inappropriately during inspiration and, in many cases, the adduction leaves behind a diamond-shaped opening, often called a posterior glottic chink (although we prefer the phrase posterior glottic gap), that is visible with video laryngoscopy and is considered diagnostic of VCD (Figure 4). We have observed the posterior glottic gap in patients with VCD; however, this finding is not universal, and its absence does not rule out VCD.

Figure 4: Inspiratory (left) and expiratory (right) video laryngoscopy views in a patient with VCD. Note the posterior glottic gap (arrow) during inspiration, representing inappropriate adduction of the vocal cords. (Photos courtesy of Nicholas J. Kenyon, MD)

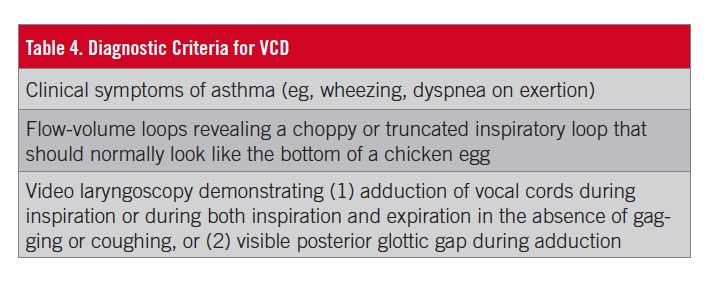

The definitive diagnosis of VCD requires direct visual confirmation of VCD by video laryngoscopy (or bronchoscopy) of involuntary and paradoxical adduction of the anterior portion of the vocal folds during both inspiration primarily and/or expiration during tidal breathing (Table 4). The procedure is performed by pulmonologists, allergists, otolaryngologists, primary care physicians, and other providers who are credentialed to perform for this invasive procedure.

During video laryngoscopy or endoscopy and direct visualization, the patient is asked to take rapid and deep inspirations or rapid alterations of sniffing and phonating to provoke VCD. Speaking sentences, panting, taking repeated deep breaths (ie, FVC maneuvers) after normal breathing, and walking up and down stairs or a ramp will often trigger VCD.

VCD IN ATHLETES

Exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction (EILO) is VCD or glottic closure that leads to a very audible, harsh inspiratory stridor during exercise, typically peaking near the end of exercise and possibly persisting during the first 5 minutes of recovery. This is unlike exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB), where wheezing or coughing begins near the end of exercise or 10 to 15 minutes afterward.

Other prominent symptoms of EILO include panic, acute respiratory distress, and prolonged inspiration. The average prevalence in the general adolescent population is 7.1%, but in athletes it is very much higher at 35.2%, and it is more common in girls and women than in boys and men.10,11

EIB and EILO may coexist in the same patient, and the rate of concomitant asthma and EILO has been reported to be as high as 56%.10

Continuous video laryngoscopy during exercise testing to physical exhaustion on a treadmill is the gold standard diagnostic test for EILO.10

NEXT: Treatment

TREATMENT

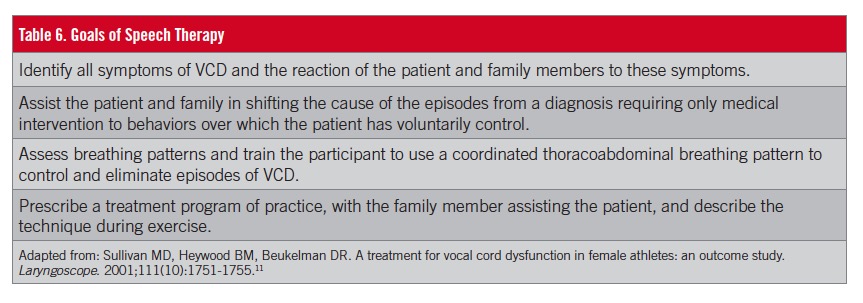

Treatment for VCD and EILO requires an interdisciplinary approach involving the primary care provider, pulmonologist, allergist, otolaryngologist, speech therapist, and even a psychologist. The approach must be individualized. (Tables 5 and 6).

Speech therapy is effective in approximately 80% of cases. Laryngeal control therapy was able to resolve symptoms or at least improve them in 88% of cases in one literature review.10 Other important treatment options for VCD or EILO are psychotherapy and botulinum toxin, and in select cases, endoscopic laser supraglottoplasty.

Ernest Pierce Stewart, DO, is chief fellow in the Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, at UC Davis Medical Center (UCDMC) in Sacramento, California.

Claudia M. Vukovich, RCP, RRT, AE-C, CCM, is coordinator of the Reversible Obstructive Airway Disease (ROAD) Center, the COPD Clinics, and the Interstitial Lung Disease Clinic at UCDMC in Sacramento, California.

Samuel Louie, MD, is a professor of medicine in the Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine at UCDMC in Sacramento, California.

REFERENCES:

- Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al; Canadian Respiratory Research Network. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317(3):269-279.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. http://ginasthma.org/2018-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/. Accessed April 11, 2018.

- Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):343-373.

- Christopher KL, Wood RP II, Eckert RC, Blager FB, Raney RA, Souhrada JF. Vocal-cord dysfunction presenting as asthma. N Engl J Med. 1983;308(26):1566-1570.

- Newman KB, Dubester SN. Vocal cord dysfunction: masquerader of asthma. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;15(2):161-167.

- Newman KB, Mason UG III, Schmaling KB. Clinical features of vocal cord dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(4 pt 1):1382-1386.

- Morris MJ, Patrick AF, Perkins PJ. Vocal cord dysfunction: etiologies and treatment. Clin Pulm Med. 2006;13(2):73-86.

- Traister RS, Fajt ML, Landsittel D, Petrov AA. A novel scoring system to distinguish vocal cord dysfunction from asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(1):65-69.

- Vukovich CM, Kivler C, Louie S. Spirometry: why, how, and when? Consultant. 2015;55(11):933-937.

- Liyanagedara S, McLeod R, Elhassan HA. Exercise induced laryngeal obstruction: a review of diagnosis and management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(4):1781-1789.

- Sullivan MD, Heywood BM, Beukelman DR. A treatment for vocal cord dysfunction in female athletes: an outcome study. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(10):1751-1755.