Richard Colgan, MD

University of Maryland

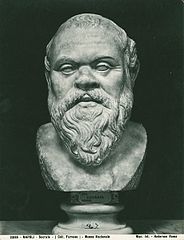

An incredible part of what we have come to understand as being important to the practice of medicine came from an era when not only Hippocrates but also Aristotle, Socrates, and Plato taught their philosophies. Many students complain about the tortuous and unpleasant experience of being asked esoteric questions, for which the answers are known largely by a more educated senior group. This ritual has even evolved its own derogatory name: “pimping.” Interestingly, this style of teaching is similar to the Socratic dialogue, attributed to the classical Greek philosopher Socrates (469 BCE–399 BCE). Put simply, it involves teaching a student by asking questions, such that the student’s answers will lead to further questions. This lends itself to understand a greater truth or a more complex lesson.

An incredible part of what we have come to understand as being important to the practice of medicine came from an era when not only Hippocrates but also Aristotle, Socrates, and Plato taught their philosophies. Many students complain about the tortuous and unpleasant experience of being asked esoteric questions, for which the answers are known largely by a more educated senior group. This ritual has even evolved its own derogatory name: “pimping.” Interestingly, this style of teaching is similar to the Socratic dialogue, attributed to the classical Greek philosopher Socrates (469 BCE–399 BCE). Put simply, it involves teaching a student by asking questions, such that the student’s answers will lead to further questions. This lends itself to understand a greater truth or a more complex lesson.

Much of what is known about Socrates comes from the writings of Plato. From the treatise The Charmides, a conversation between Socrates and a young boy, we learn of the importance of temperance. This is a very significant lesson in medicine; in fact, it provides the foundation upon which medicinal practice is built. Medicine is derived from Indo-European med-, to take appropriate measures.1 From the Latin mederi, to look after, heal, and cure, stemmed the words medicine and remedy. Other derivates led to the words modern, modest, and moderate. We are urged by Socrates to be temperate, and as healers we can sometimes do the best for our patients by doing the least. As physicians, we become true practitioners of the healing art when we recognize the potential for illness and disease to improve naturally with time and overcome the urge to provide unnecessary physiological therapy. Surgeons in particular are aware of this, the best of whom help their patients by declining an opportunity to operate, in instances when they know it will not benefit the patient.

The word doctor is derived from the Indo-European root dek-, to take, to accept, via the Latin docere, to teach.2 It is critical to the physician–patient relationship that we understand the impact and power of our ability to teach our patients. It is too often overlooked. An important lesson for the young healer is to recognize that often it is not “the pill in the hand, but the hand behind the pill” that helps our patients feel better.3 It is important that we educate our patients about their health so that they may better take care of themselves. A 1998 survey looking at prescription of antimicrobials highlighted this concept. In evaluating attitudes of parents and physicians concerning the prescribing of antimicrobials to a pediatric population, 65% of patients expected to receive an antibiotic for treatment of an upper respiratory infection.4 In this study there was no correlation between patient satisfaction and receipt of an antibiotic prescription.4 Instead, patient satisfaction correlated highest with the quality of the physician–patient interaction. Results from focus groups indicate that patients would be satisfied if an antibiotic was not prescribed as long as the physician explained the reasons for the decision to withhold antibiotics.4 It has also been shown that patients who are informed have lower anxiety and complication rates, compared to those who are uninformed.5-8 This is docere in action!

Another important art we can cultivate in our office visit is to consider asking our patients if there is anything about their illness which they are particularly concerned about. Many patients fear that the symptom they are experiencing may represent something terrible or fatal, which may in fact not be the case at all. Reassurance that in your experience a certain symptom is not at all likely to cause a certain terrible outcome is sometimes the major agenda, which our patients have in making an appointment to see us, even if this concern is not clearly communicated. Other patients focus on what may seem to us as mundane or simple worries, but to the patient addressing these concerns may make all the difference in his or her personal interpretation of the healthcare encounter, its effectiveness, its success, and your abilities as a physician. Being a good prognosticator is truly valued.

During the office visit, it is our responsibility to teach our patients what they can do to take better care of themselves. This may entail specific and clear recommendations about diet, exercise, social habits, such as smoking and drinking or other activities. An excellent way to open the discussion toward teaching your patient is to simply ask them at the end of your visit, “Do you have any questions for me?” We should be clear in giving our opinion as to when they should return in follow up—be it as needed, in 3 months, if condition worsens, etc.—and must strive to set reasonable health goals with our patients to emphasize the partnership we are forming to improve their health. Understanding that we are teachers is critical to mastering the healer’s art. From the Indo-European root dek- of the Latin word docere also comes the word discere, to learn, from which we get the current derivation disciple.2 Dignity and decent are also derived from the same Indo-European root. As doctors we are our patients’ teachers and must provide them with the environment to learn so as to better their physical and mental wellness. Hippocrates teaches us to be a student of nature, life, and illness by observing all. Others have described this full circle of education by saying “You can’t be a good teacher unless you are a good student.” We will look further into the importance of being a good student in the next chapter.

NEXT BLOG: MEDIEVAL MEDICINE: WHAT WE’VE LEARNED FROM THE DARK AGES

Richard Colgan, MD, is associate professor of family and community medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland. He was the School's nominee to the Association of American Medical Colleges for its Humanism in Medicine Award, the recipient of numerous faculty teaching awards including the School's Golden Apple Award for excellence in teaching. Dr Colgan is the author of Advice to the Young Physician: on the Art of Medicine. For more information, go to www.advicetotheyoungphysician.com.