Chronic Kidney Disease Management: Where Are We?

AUTHOR:

James Matera, DO, FACOI, is a practicing nephrologist, Senior Vice President for Medical Affairs, and Chief Medical Officer at CentraState Medical Center in Freehold, New Jersey.

CITATION:

Matera J. Chronic Kidney Disease Management in 2022: Where Are We? Consultant360. Published online March 14, 2022.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) remains a significant concern in the United States and globally, with 15% of US adults—more than 37 million patients—affected. In addition, many people who have underlying CKD may not be aware of it, which adds even more to the disease burden, progression, and economic impacts that come with this disease.1 Over the last few years, there have been advances in the field that are proving to be game-changers, so hopefully, we will start to see improvements in diagnosing, treating, and managing CKD. This article highlights a case presentation of a patient with CKD and reviews recent advances and outcomes data.

Case Presentation

A 42-year-old Black woman with a medical history of type 2 diabetes presents at your office. She had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at age 25 years with complications including retinopathy and nephropathy.

She has resistant hypertension, significant proteinuria, coronary artery disease with 2 stents placed at one time, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), and secondary hyperparathyroidism related to CKD. She follows up with her primary care physician (PCP) 2 to 3 times per year and with her nephrologist annually. At her last office visit to her PCP, she reported worsening edema, mild dyspnea, and general fatigue.

Upon physical examination at current visit, her blood pressure (BP) was 178/94 mm Hg, pulse was 76 beats/min, and respiratory rate (RR) was 18 breaths/min. Results of a chest examination revealed a grade 2/6 holosystolic murmur and no gallop. Her extremities had grade 2+ pitting edema of both legs to the knees. A review of her current medications, which she reports nonadherence at times, include:

- Valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide, 300mg and 25 mg daily, respectively

- Metoprolol, 100 mg daily

- Doxazosin, 4 mg daily

- Nifedipine, 90 mg daily

- Insulin, 32 units at night and sliding-scale before meals

- Glimepiride, 4 mg daily

- Aspirin, 81 mg daily

Laboratory results at the office visit showed levels of sodium at 142 mmol/L, potassium at 5.6 mmol/L, chloride at 118 mmol/L, bicarbonate at 15 mmol/L, calcium at 9.7 mmol/L, phosphorus at 6.5 mmol/L, and parathyroid hormone at 924 ng/L.

Urinalysis results show a protein-to-creatinine ratio of 3200 mg/g. Hemoglobin level was low at 10.4 g/dL; ferritin level was low at 87 μg/L;and iron saturation was low at 10%. An electrocardiography scan was conducted, results of which showed a normal sinus rhythm and no acute changes or peaked T-waves. Blood urea nitrogen is 65 μmol/L, creatinine is 3.2 μmol/L. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is 9.2%.

At this point, you should ask yourself these questions:

- What stage CKD is this patient, and does her Black race play a role?

- Are you treating her for diabetes and diabetic kidney disease as best as you can?

- How will end-stage renal disease (ESRD) treatment impact this patient?

- Would she be a transplant candidate?

Race/Ethnicity and the eGFR

The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) has been reported for 20 years, and it helps categorize patients into stages of CKD from 1 to 5.2 This data has included demographics such as age and race, and has always given higher values to Black patients, potentially underestimating the actual GFR in this patient population. The other methodology for calculating eGFR includes cystatin-C but does not include race and has the same accuracy as the creatinine-based formula.3

In 2021, the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration published an article on eliminating race as a variable when calculating eGFR. Their study results showed that newer equations for calculating eGFR incorporate creatinine and cystatin-C without including race. These equations were defined similarly between Black patients and all others, hopefully limiting underestimation of CKD issues.4

Optimizing Diabetes Management for Diabetic Renal Disease

We know that sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors improve glycemic control by inhibiting both glucose and sodium reabsorption in the proximal tubule.5 The initial results of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME and CREDENCE studies demonstrated protection against cardiovascular events and renal end points, including positive effects on albuminuria, serum creatinine progression, ESRD, and risk of death. These studies led to a cadre of other studies that utilized these agents and demonstrated positive effects, leading practitioners to use SGLT2 agents for both patients with diabetes and without diabetes.6,7

The results of a large study published in 2021 also showed racial and socioeconomic differences in patients who were prescribed SGLT2 agents.8 The results of this cohort study showed that the number of prescriptions for SGLT2 agents was lower among Black women with lower socioeconomic status compared with other patient populations.8 This suggests that this group needs interventions focused on ensuring equity for agents known to improve outcomes.

For patients with advanced-stage 4 CKD, the results of the DAPA-CKD trial showed the SGLT2 agent dapagliflozin had significant benefits, including reduction of risk of renal failure and improved survival in patients with or without documented diabetes.9 Prescribing dapagliflozin for patients with stage 4 CKD showed a 27% reduction in the primary endpoint (> 50% sustained decline in eGFR, ESRD, or death from cardiovascular disease), extolling the benefits of these agents, even in more-progressive renal disease.10

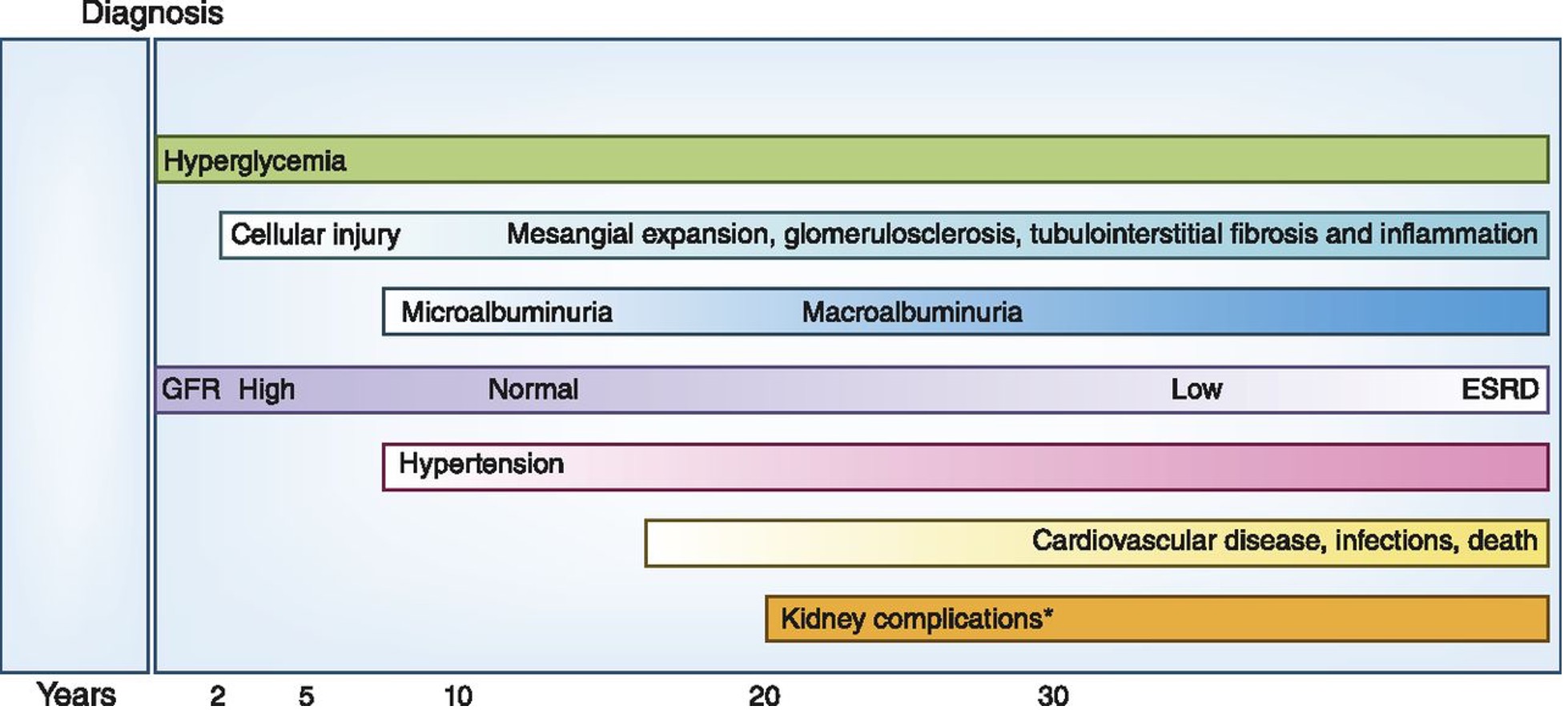

Diabetic renal disease will occur in about 40% of patients with diabetes. During the natural history of the disease, there are various points where cellular injury can occur, giving us a few pathways to try to lessen the burden of chronic disease.11As CKD progresses, renal and nonrenal complications develop earlier than they do in other types of kidney disease.11 Issues with glycemic control, cellular injury, albuminuria, and cardiovascular complications occur across the spectrum and can occur at variable times (Figure 1).11

Figure 1. The natural history of diabetic kidney disease and the various cellular level effects where renal damage occurs over time. These are the potential areas where we can impact disease progression.

End-Stage Renal Disease Choices

While we will strive to preserve renal function for as long as possible, the patient is likely going to require renal-replacement therapy in the near future. She is already exhibiting signs of advanced CKD effects, including mild anemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism (including inherent risk on cardiovascular and bone disease), and azotemia. She has reported not adhering to all medical treatments, and that will certainly impact our decisions when developing a management plan for ESRD.

This will require much time and effort to be successful, and shared decision-making must take center stage. Since the presidential executive order in 2019, there has been an emphasis on treating patients undergoing dialysis at home, including using home modalities such as home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis.12 The goal is to treat 80% of patients undergoing dialysis with a home modality or a kidney transplant by 2025.13

In populations with socioeconomic disadvantages, the uptake of home therapies is much lower. Many factors play a role, including unstable housing and low medical literacy. Utilizing proactive training, early education, and shared decision-making can increase the likelihood that home modalities are chosen.13

With issues such as training, adherence, potential infection, and glucose intolerance in patients with diabetes, a long-standing debate has been whether peritoneal dialysis improves outcomes. In a recent review, the New England Journal of Medicine reported that both peritoneal and hemodialysis are associated with similar survival rates and similar quality-of-life factors.14 Factors that lead to a lower rate of acceptance of peritoneal dialysis are often provider-driven, with a lack of training in some programs leading to a knowledge gap.14

Shared decision-making is a concept that needs to be applied in these training programs. This concept and process leads to patient satisfaction and adherence and may help us move toward those proposed goals for 2025.15 The 3 steps needed to develop a training program like this include initial preferences, deliberation, and informed preferences (Figure 2).15 Developing and implementing a shared decision-making program must include insight from and communication between the PCP, the nephrologist, the patient. This type of decision making needs to be fluid as time goes on to account for adverse effects during disease progression.

Figure 2. A shared decision-making model describing modalities of communication. A patient will likely be more proactive in adherence to the medical treatment plan if we use the patient’s preferred method of communication and involve the patient in every step of the decision-making process.15

Kidney transplantation is another option either before or after dialysis. Unlike the aforementioned issues regarding outcomes across types of dialysis modalities, renal transplantation is associated with improved outcomes. In patients with diabetes, the renal survival rates over the years have improved with both deceased donor and living donor transplants.16 Of course, the patient trades the dialysis lifestyle for a lifetime of immune-modulating medications and the issues they cause. Certainly the current COVID-19 pandemic has proven that the transplant population is at high risk for severe COVID-19 infection, as they do not mount adequate antibody responses to the COVID-19 vaccine.17

In the United States, there is continued improvement in long-term allograft and patient survival with the ability to quickly diagnose rejection using biomarkers, improvement in immune-modulating medications, and T-cell-directed therapies for viral infections like BK polyomavirus. Antirejection therapy is also becoming more focused on T-cell, antibody-mediated, and desensitization protocols.18

With our patient, social and racial disparities exist that need to be overcome. Black individuals make up 33% of the transplantation list but have higher wait times, higher incidences of diabetes (new-onset diabetes is not a concern for our patient), and lower graft survival compared with White individuals.19 We need to work on these disparities as a society to enable the same level of access to care despite varying genetic and social determinants of health.

Reducing Gaps in Care 2022

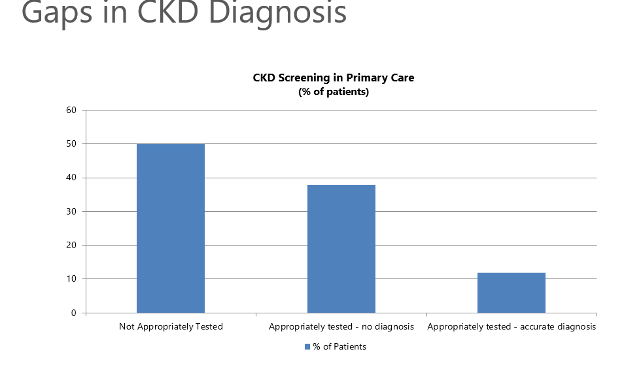

One thing we can plainly see is that prevention, early detection, and management of CKD is essential. It is time for PCPs and nephrologists to collaborate on this group of patients, with a focus on reducing progression and cardiovascular risks, and making shared decisions when it comes to dialysis. In a 2014 study of more than 9000 patients, 5036 (54.1%) had stage 1 to 5 CKD based on eGFR and albuminuria; however, CKD was formally diagnosed in only 607 (12.1%) patients (Figure 3).20 This inability to assign a formal diagnosis prevents CKD from being at the forefront of the care of these patients.

Figure 3. The graph shows nearly half of our patients are not screened appropriately for CKD, and many are screened but the diagnosis of CKD is never entered into their medical record.20

Conclusions

When we think about the above data and situations, we can see that patients with CKD have gaps in care. When looking at a US dataset, patients with CKD also had more uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes, and statins were not as likely to be prescribed according to guidelines.21 The impact that this has on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is evident, given that patients with CKD also have, and usually die from, cardiovascular-related issues.21

Our patient discussed herein would benefit from some of the discussion points that we have reviewed here today. All aspects of care need to have the risks and benefits assessed, accounting for any racial and population health disparities and assessing outcomes. Clinical decision-making should be a group activity, with input from all relevant specialists as well as the patient. Here is a take-home note: if we do not know the disease exists, then it will be impossible to alter the progression and outcomes.

References:

- Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States, 2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 4, 2021. Accessed January 27, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/publications-resources/ckd-national-facts.html

- Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function — measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(23):2473-2483. doi:10.1056/nejmra054415

- Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):20-29. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1114248

- Inker, LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, et al. New creatinine- and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1737-1749. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2102953

- Tuttle KR, Brosius FC 3rd, Cavender MA, et al. SGLT2 inhibition for CKD and cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: report of a scientific workshop sponsored by the national kidney foundation. Diabetes. 2021;70(1):94-109. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.08.003

- Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, et al; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators. Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):323–334. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1515920

- Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al.; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2019;380(24):2295–2306. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1811744

- Eberly LA, Yang L, Eneanya ND, et al. Association of race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor use among patients with diabetes in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e216139. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6139

- Petrykiv S, Sjöström CD, Greasley PJ, Xu J, Persson F, Heerspink HJL: Differential effects of dapagliflozin on cardiovascular risk factors at varying degrees of renal function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(5):751-759. doi:10.2215/cjn.10180916

- Chertow, GM, Vart P, Jongs N, et al; DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators. Effects of dapagliflozin in stage 4 chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(9):2352-2361 doi:10.1681/asn.2021020167

- Alicic RZ, Rooney MT,Tuttle KR. Diabetic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(12): 2032-2045. doi:10.2215/cjn.11491116

- Medicare program; specialty care models to improve quality of care and reduce expenditures. Federal Register. July 18, 2019. Accessed January 27, 2022. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/07/18/2019-14902/medicare-program-specialty-care-models-to-improve-quality-of-care-and-reduce-expenditures

- Flanagin EP, Chivate Y, Weiner DE. Home dialysis in the United States: a roadmap for increasing peritoneal dialysis utilization. Am J Kid Dis. 2020;75(3);413-416. doi:10.1681/asn.2021020167

- Teitelbaum I. Peritoneal dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1786-1795. doi:10.1056/nejmra2100152

- Yu X, Nakayama M, et al. Shared decision-making for a dialysis modality. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;7(1):15-27. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.019

- Matas AJ, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2011 annual data report: kidney. Am. J. Transplant. 2013;13 Suppl 1:11–46. doi:10.1111/ajt.12019

- Caillard S, Thaunat O. COVID-19 vaccination in kidney transplant recipients. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021;17(12):785–78. doi:10.1038/s41581-021-00491-7

- Hariharan, S, Israni, AK, and Danovitch, G. Long-term survival after kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(8):729-743. doi:10.1056/nejmra2014530

- Harding K, Mersha TB, Pham PT, Waterman AD, Webb FA, Vassalotti JA, Nicholas SB. Health disparities in kidney transplantation for African Americans. Am J Nephrol. 2017;46(2):165-175. doi:10.1159/000479480

- Szczech L, Stewart RC, Su HL, et al. Primary care detection of chronic kidney disease in adults with type-2 diabetes: the ADD-CKD study (awareness, detection and drug therapy in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease). PLoS One. 2014. 26;9(11):e110535. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110535

- Tummalapalli SL, Powe NR, Keyhani S. Trends in quality of care for patients with CKD in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(8):1142-1150. doi:10.2215/cjn.00060119